What Homelessness Looks Like Here in Four Charts

In 2002, when the Bush administration started pushing cities to adopt 10-year plans to reduce homelessness, Seattle/King County was already on board.

The feds suggested targeting chronic homelessness – typically the most visibly homeless people. But Seattle was ambitious and promised to end all homelessness by 2015.

It’s been 10 years since the Seattle plan was launched, and the number of homeless people here has surged. This isn’t a national trend – across the county, homelessness has dropped by nearly a quarter.

The numbers aren’t relenting, either. A count of the homeless in January revealed that the number of people living outside rose 22 percent over last year in the city of Seattle.

Where Do Seattle's Unsheltered Homeless Spend The Night?

CREDIT KUOW GRAPHIC/KARA MCDERMOTT

Competing Plans

Cities had an incentive to draft 10-year plans: government money.

Here’s how it works: Communities compete with each other for federal dollars to fight homelessness. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, let them know that those with 10-year plans would have a leg up.

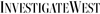

How Do We Compare Nationally?

CREDIT KUOW GRAPHIC/KARA MCDERMOTT, PHOTO/JOHN RYAN

Even With Plans In Place, Homelessness Grows

How do you wrap your mind around 18,839 homeless people in Washington state?

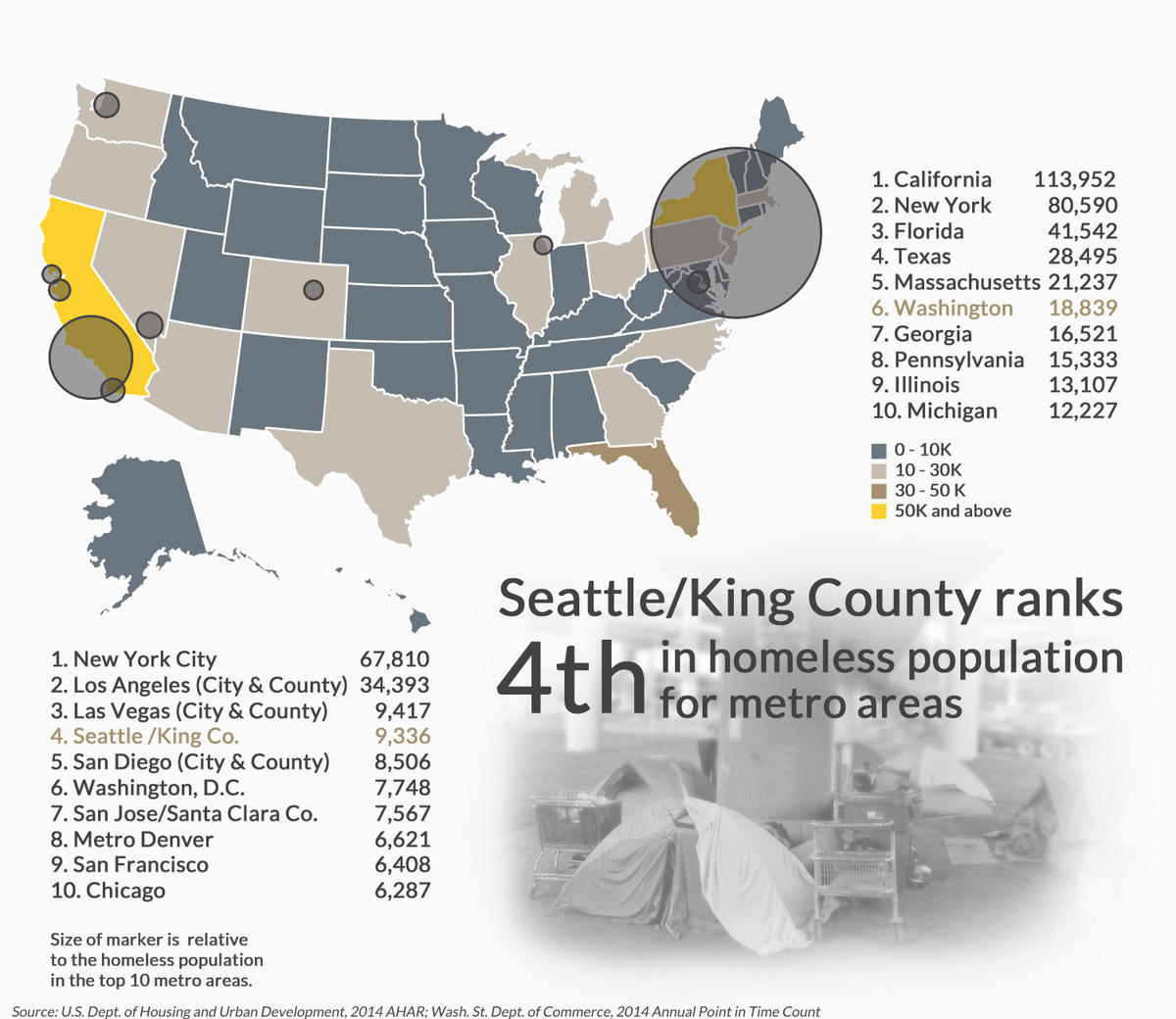

Washington’s homeless rate has actually been going down since 2006. But King County’s rate has been going up, and it’s outpacing the general population growth.

According to the US Census, King County’s population has increased about 12 percent since 2006, while its homeless population has gone up 18 percent.

And while the county accounts for about a third of the state’s population, it represents half of its homeless.

CREDIT KUOW GRAPHIC/KARA MCDERMOTT, PHOTO/JOHN RYAN

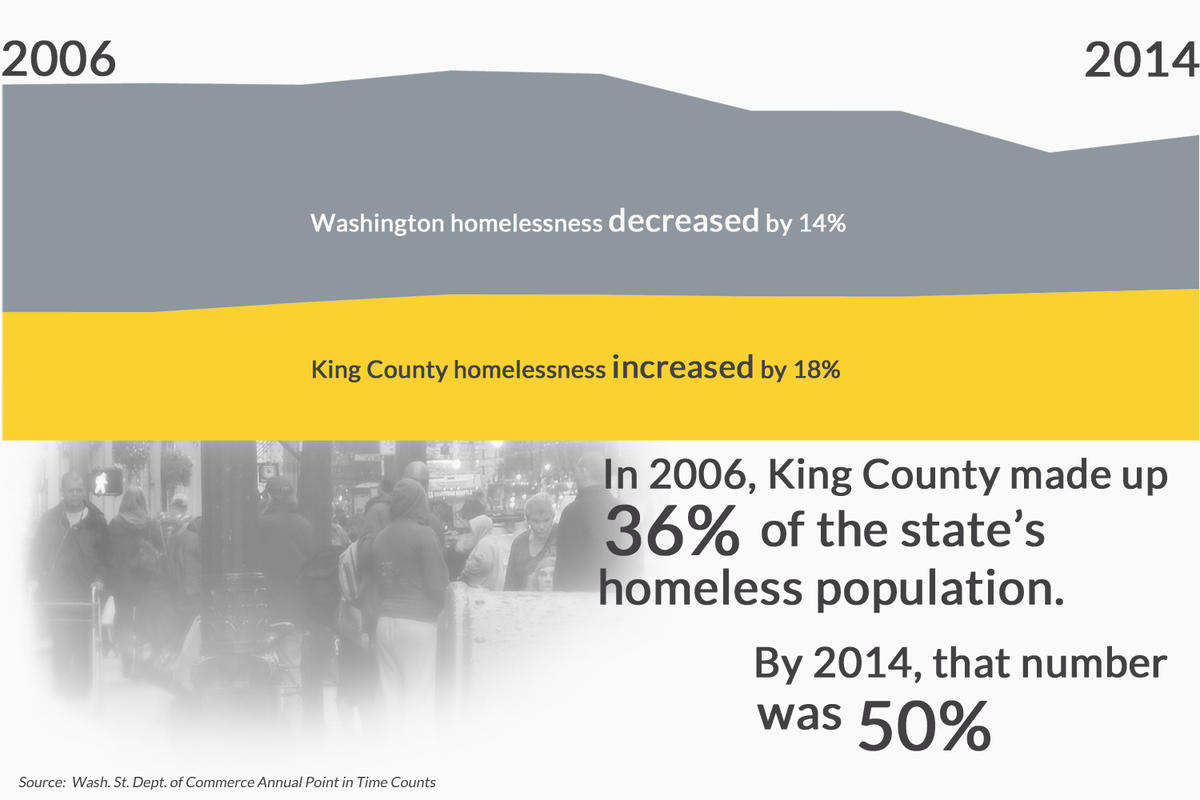

Who Are The Homeless Here?

Let’s break it down further. King County’s One Night Count in 2014 revealed that 1,754 minors were living in emergency shelters or transitional housing: more than a quarter of the total people counted.

That’s not the only disparity. While African-Americans make up only about 7 percent of King County’s general population, they are the most represented race in emergency shelters or transitional housing.

CREDIT KUOW GRAPHIC/KARA MCDERMOTT, PHOTO/JOHN RYAN

What Went Wrong?

The 10-year plan didn’t exist in a vacuum, of course. There were larger forces that helped derail the plan: the recession, massive cuts to mental health and substance abuse programs.

People were laid off, lost their housing and wound up surfing on couches, camping in car or living on the streets.

And then, as the economy recovered, Seattle boomed into a tech hub. Grittier parts of our city, where housing had been more affordable, turned into high-rent districts that attract well-paid workers.

InvestigateWest contributed to this report.

The story you just read is only possible because readers like you support our mission to uncover truths that matter. If you value this reporting, help us continue producing high-impact investigations that drive real-world change. Your donation today ensures we can keep asking tough questions and bringing critical issues to light. Join us — because fearless, independent journalism depends on you!

— Jacob H. Fries, executive director

DonateCancel anytime.