Two Colville women were booked into a rural Washington jail. It became a death sentence

Critics say WA jails are letting opioid users suffer from withdrawals, leading to preventable deaths

Washington defendants owed nearly $300 million as of July 2023

A new study shows that the amount of legal financial obligations ordered by Washington courts decreased by nearly 70% between 2018 and 2021, due in part to new laws limiting the practice and fewer cases filed throughout the pandemic.

But Washington defendants still owe nearly $300 million as of July 2023, according to the state-funded report by the Washington State Center for Court Research, with wide variation across the state for when, how and which monetary sanctions are placed on defendants. These variations are due, in part, to Washington’s decentralized court system, which allows courts throughout the state — and judicial officers — to operate largely independently of one another.

For years, criminal justice reform advocates and lawmakers in Washington have worked to limit the amount of legal financial obligations, collectively called LFOs, that can be placed on defendants. Common LFOs include mandatory fees meant to recoup the cost of services such as DNA testing and public defenders; fines intended as punishment for specific crimes; and restitution, which is meant to compensate a victim for damages or losses. The debt, which depending on the type of LFO can balloon with interest, can be crippling and can make finding stable housing, employment and upward mobility significantly more challenging long after incarceration.

Many of the legislative reforms have centered on fines and fees, with restitution remaining largely untouched. In 2018, interest for non-restitution LFOs was removed and lawmakers made more fines and fees discretionary for those unable to pay. Most recently, in 2023, the Legislature waived all debt from non-restitution LFOs in juvenile courts.

Washington relies on LFO revenue to fund local court operations, ranking 48th in the country for state-level judicial funding, according to the report. Judicial funding in most states comes from revenue streams such as income taxes, which Washington does not have.

In 2019, Washington ranked second among all states in the amount of LFO debt owed by defendants, the report said.

“Hopefully the report is developing the sort of common platform of getting people on the same page and saying, ‘Yeah, sure, there was legislation in 2018, and we can see some impact. But this is an ongoing issue,’” said Karl Jones, the equity senior research associate with Washington State Center for Court Research who helped put together the report.

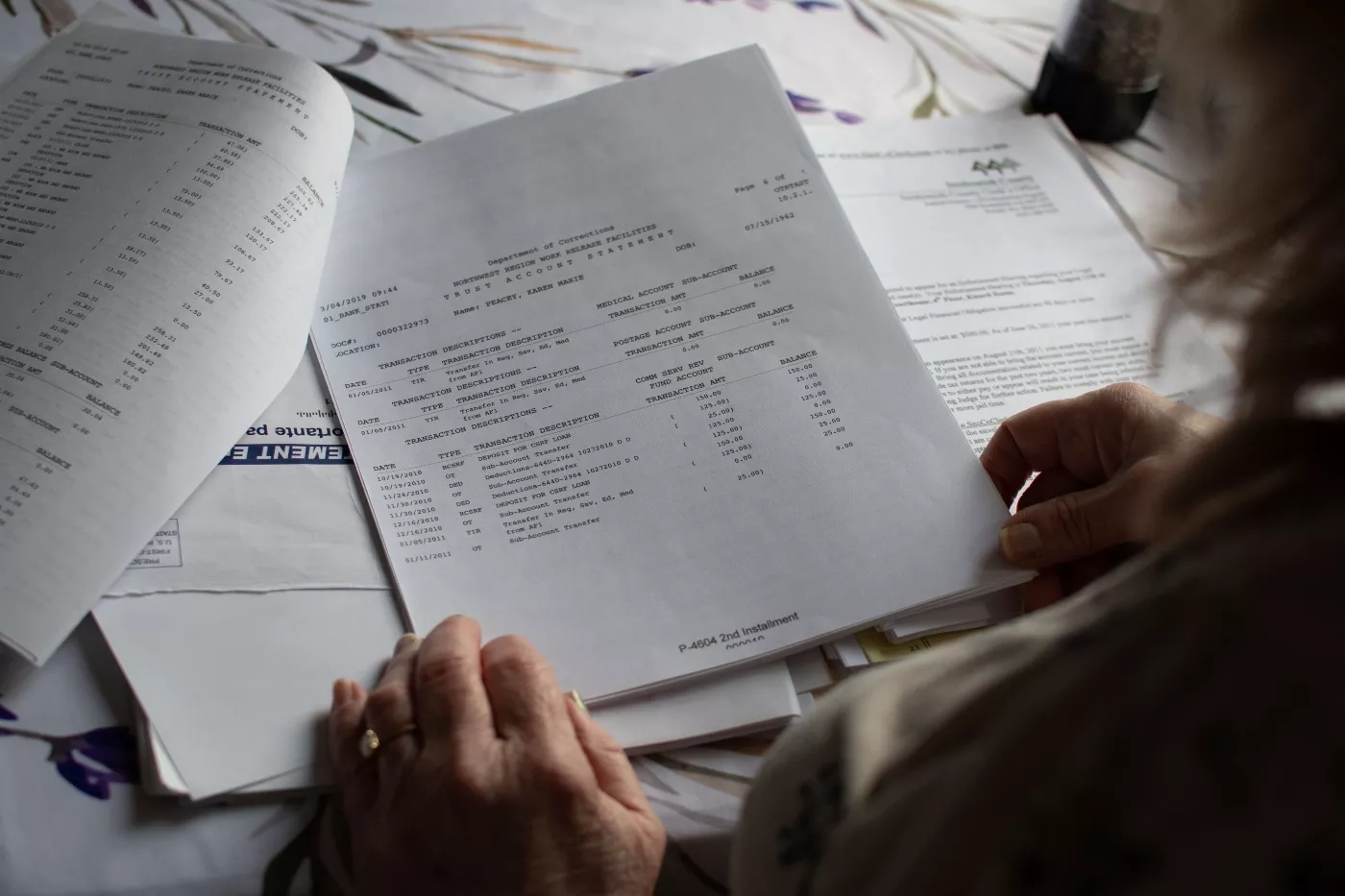

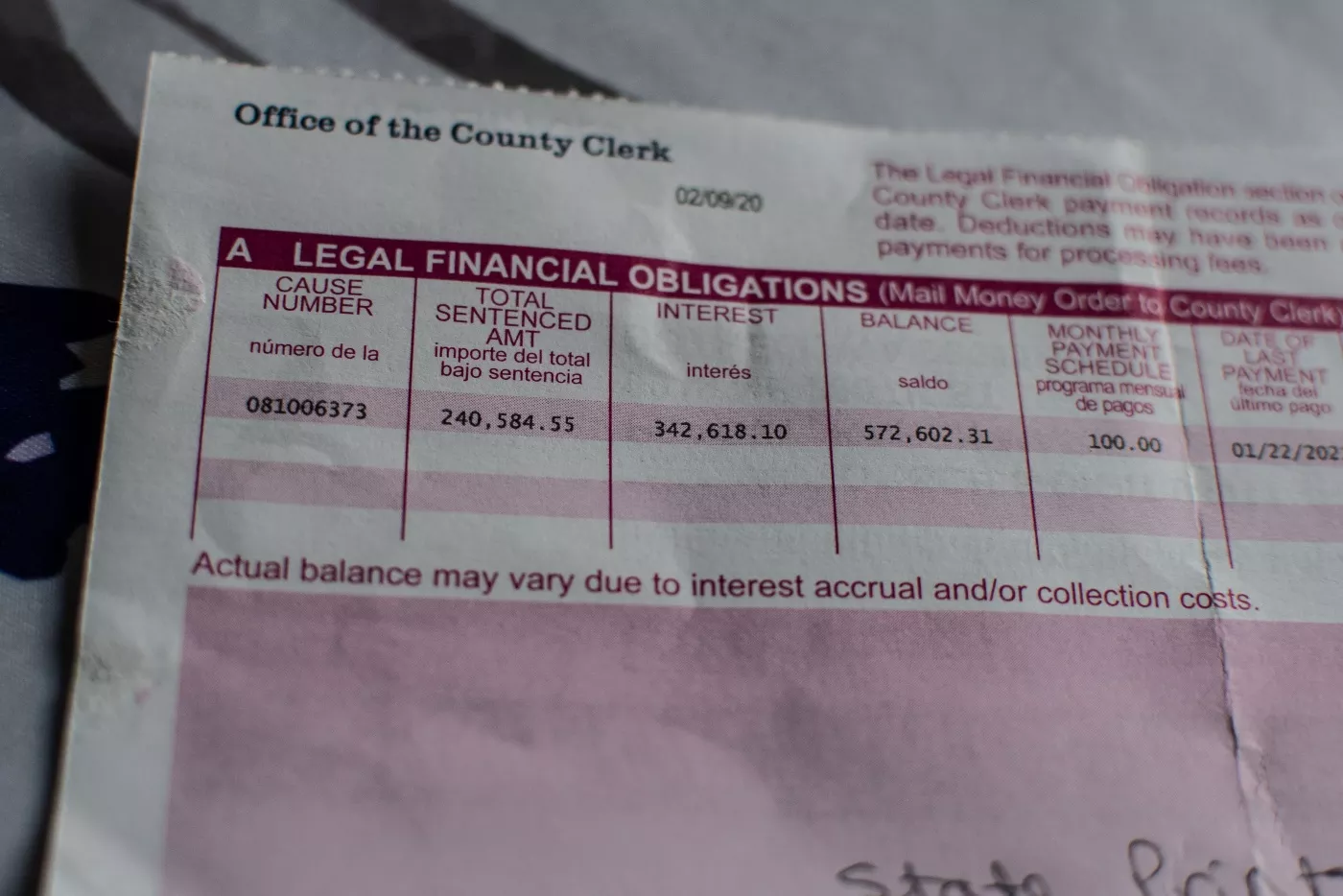

Karen Peacey, 62, said it’s still an issue for her. In 2008, she was ordered to pay $250,000 in restitution for a financial crime she committed against a private business. Today, the debt has ballooned to nearly $1 million.

Paying down her debt while in prison was impossible. She worked various jobs behind bars: in the kitchen, as a maintenance person and on the outdoors crew making between 34 and 39 cents an hour. After she was released from prison in 2011, she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and was unable to work. For years, she struggled to pay her $100 a month payment until a lawyer helped petition the court to pause her payments given her disability status and lack of income. But her debt is still incurring interest.

“Every three months, you get this envelope saying you owe astronomical amounts, and it keeps rising,” Peacey said. “I made a mistake, and I shouldn’t have done it. I take responsibility for it, but I shouldn’t have to pay for life. I shouldn’t have this hanging over me for life.”

Questions raised

The nearly 300-page report took a comprehensive look at LFOs issued throughout the state’s Superior Courts, Juvenile Courts, and Courts of Limited Jurisdiction — which can include municipal, family, small claims or traffic courts. It was built off a 2022 report by the Washington State Supreme Court Minority and Justice Commission, but the 2024 report is unique in that it looked at not only when restitution was ordered, but also where the money goes.

The researchers found the largest portion of LFOs are directed at insurance companies, particularly in adult Superior Courts.

“There were discussions amongst legislators and within the community, sometimes speculating, that a lot of money was going to insurance companies, which some people felt was inappropriate,” said Lindsey Beach, an LFO research associate at the Washington State Center for Court Research who co-authored the report.

Not all states allow insurance companies to be listed as the victim of a crime, but Washington does. For example, California does not allow an insurance company to be named as a victim in a restitution case unless they were a direct victim, not acting on behalf of a policyholder.

“If somebody makes an insurance claim, the insurance pays out their claim. But separate from that, the insurance company can also say, ‘We were harmed because we had to pay this claim. And so you owe us money,’” explained Karin Martin, a crime policy specialist and associate professor at the University of Washington’s Evans School of Public Policy & Governance. “It’s separate from the person who was directly harmed by a crime.”

The insurance company also receives premiums from policyholders to cover claims, Martin added.

Adult Superior Courts assessed defendants $108 million in restitution for cases filed between 2018 and 2021. Almost one-third of that money, $33.45 million, was assigned to insurance companies. And just four of those courts generated 51% of all restitution assessed to insurance companies: Whatcom, Clark, Mason and Snohomish.

The state-funded study published in December found that particular courts order a disproportionate amount of their overall restitution to themselves, local law enforcement agencies and the Washington State Patrol, with some courts ordering restitution up to eight times more frequently than others.

At all three court levels, judicial officers assessed $2.7 million in restitution to local courts and law enforcement agencies between 2018 and 2021 — and $2.4 million to the Washington State Patrol.

The study builds on existing research that has found that LFOs disproportionately impact low-income people and communities of color, often pushing people into cycles of debt that make finding housing, financial security and employment significantly more challenging. Unpaid fines and fees can also lead to further involvement in the criminal justice system.

“It's a problem that so much (restitution) is going to state agencies and law enforcement,” said Kelly Olson, the policy director for Civil Survival, a nonprofit that advocates and provides legal aid to formerly incarcerated people in Washington. “The big thing with LFOs is you cannot vacate your record or do anything like that until you’ve paid off all your LFOs.”

Racial disparities and ‘justice by geography’

While legislation has helped to limit LFOs, clear disparities exist along racial and ethnic lines, as well as geographic location.

In limited-jurisdiction courts, Latino defendants receive the highest proportion of LFOs on average. They also carry the highest average outstanding debt amounts, according to the report. A high percentage of cases with Native American defendants in courts of limited jurisdiction have outstanding debt, at 62% compared to the statewide average of 43%.

During the study period, juvenile courts imposed the highest average LFO amounts on cases with Black youth, over twice the amount of the lowest average amount for cases with Asian/Pacific Islander youth. This contrasts with patterns in superior and limited-jurisdiction courts, where cases with Black adult defendants have the lowest average LFO imposition amounts.

The researchers also found that courts were roughly three times more likely to reduce LFO debt for defendants in wealthier neighborhoods versus high-poverty areas.

Some reasons a court might reduce someone’s debt could be due to a clerical error, if the defendant died, or if a defendant successfully petitioned the court to reduce their debt due to change in circumstances such as an inability to pay or legislative changes that would impact their debt, Beach explained.

“This pattern is potentially concerning,” the researchers wrote in the report. If debts were being reduced because defendants couldn’t afford to pay, the data should show the most reductions in the poorest neighborhoods.

“Here, we observe the opposite,” they wrote.

According to the Vera Institute, 78% of people in Washington with LFO debt meet the state’s indigency standard, meaning they receive an annual income of 125% or less of the federal poverty level. For a family of four, that would be $39,000 a year in household income, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Due to recent legislation, courts cannot impose some LFOs on indigent defendants. However, systematic data on defendants’ indigency status isn’t readily available. It’s a topic the researchers hope to explore further.

“On our end, it was like, ‘Oh, we've discovered a new black box,’” Beach said, regarding disparities in LFO reductions at the neighborhood level. “It’s something we want to look into.”

The state-funded study highlights other strategies that could help limit the burden of LFOs on defendants, like limiting what crimes are eligible for LFOs, as California did in 2024 and New Mexico did in 2023. The state could wipe away uncollected debt for adults like Delaware and New Jersey recently did. Or most notably, the researchers wrote, the state could limit the amount of revenue that’s allowed to be generated by LFOs, a step Missouri took in 2015.

“We have courts that are still very heavily charging LFOs,” said Olson, the policy manager at Civil Survival. “It’s not fair. Everybody should be able to get relief.”

A bill proposed in 2022 sought to waive restitution owed to any entity that wasn’t an individual for cases in the state’s Superior Courts. But it was ultimately narrowed to only include restitution owed to insurance companies and state agencies. Civil Survival hopes to bring a bill this legislative session that would limit the discretion allowed by judges in issuing LFOs, including for restitution.

“People inside (prison) are only making $1 an hour, and so having people leave with mountains of debt as soon as they come out … it doesn’t make sense,” she added.

The story you just read is only possible because readers like you support our mission to uncover truths that matter. If you value this reporting, help us continue producing high-impact investigations that drive real-world change. Your donation today ensures we can keep asking tough questions and bringing critical issues to light. Join us — because fearless, independent journalism depends on you!

— Jacob H. Fries, executive director

DonateCancel anytime.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters and never miss an investigation.