Lawsuit alleges Bureau of Indian Affairs officers “executed” unarmed Shoshone-Paiute man in Idaho

The lawsuit claims Bureau of Indian Affairs officers lacked jurisdiction when they pursued, killed Cody Whiterock

Free toys sent home with kids in Idaho’s Valley County, along with flyers boosting the sheriff in days before election

Days before early voting started in the Idaho Republican primary this spring, Valley County Sheriff Kevin Copperi was at Barbara Morgan Elementary School handing out a literal truckload of free toys to kids.

One by one, over 400 children got to pick from a treasure trove — pickleball paddles, plastic tennis rackets, dominos, brainteasers, toy semi trucks, Spider-Man art sets and all sorts of Encanto playsets. All were donated by Toys for Tots, a Marine Corps program formed to give toys to children who can’t afford them. Valley County, a rural area of about 12,000 two hours north of Boise, isn’t particularly low-income. The largest town is McCall, a resort town next to a ski mountain.

These kids also got something extra to take home to their parents: a flyer from the “Toys for Tots Plug and Unplay Team.” One side touted a presentation that the Marines and Copperi gave about how the Marines and Constitution play a role “ensuring every American is able to live a life of Freedom.” The other side featured a nearly full-page photo of Copperi, with “THANK YOU Sheriff Kevin Copperi” spread out across big letters across the bottom.

Hundreds of students at three other elementary schools got similar flyers.

To Brad Beaman, one of Copperi’s primary opponents, the sheriff’s intent was obvious: a campaign event disguised as a toy giveaway for needy children.

“I thought, this guy is pulling out all the stops. Why would you do this two weeks before the primary if it wasn’t a political move?” Beaman said. “A lot of parents were really upset.”

When the May primary vote was tallied, Copperi won, besting Beaman by only 76 votes out of nearly 2,800.

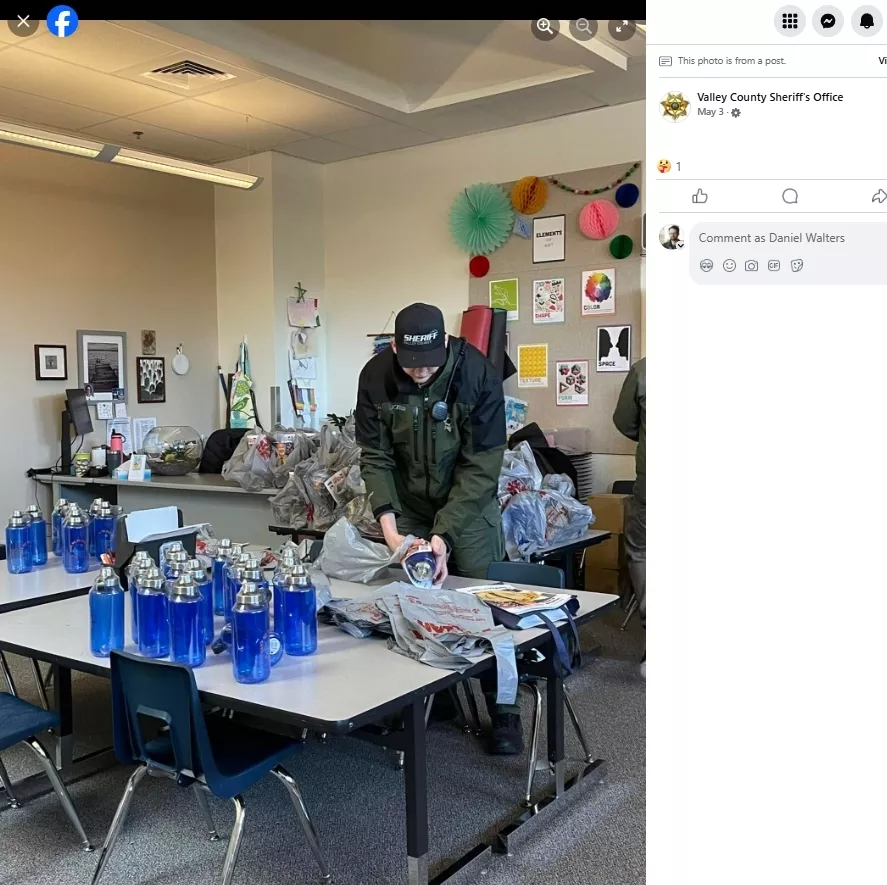

Copperi told InvestigateWest that the giveaways were intended to help kids, and he denied any involvement in producing the flyer — though a photo posted on his Facebook page showed a deputy wrapping a flyer around a water bottle to send home with kids.

Instead, he said he believes the flyers came from the same person who asked him to contact the schools in the first place: Tim Flaherty. Flaherty not only runs the nonprofit that helps Toys for Tots store and distribute toys, he’s also a political consultant for some of the most prominent politicians in the region. By the time the general election was held, Copperi had paid more than $55,000 to Flaherty’s firm to run nearly every aspect of his campaign.

It’s just one example of how Flaherty has blurred the lines between his role as the leader of the nonprofit Astegos — banned from making political endorsements under the federal tax code — and his role as a political consultant to some of the most influential figures in southern Idaho.

To report how Flaherty has used the name — and toys — of Toys for Tots to benefit his political clients and his own nonprofit, InvestigateWest dug through campaign finance reports, court filings and social media posts, interviewing nonprofit workers, political leaders and Toys for Tots Marines. Flaherty declined to answer a long series of questions from InvestigateWest on the record.

Flaherty, convicted of federal wire fraud in 2009, is a controversial figure within the world of Boise-area nonprofits — charismatic and ambitious, but dogged by accusations of dishonesty, irresponsibility and self-dealing from some nonprofit workers.

Jodi Peterson-Stigers, executive director of Interfaith Sanctuary, where Flaherty previously served as assistant director, once called him a “great business mind.” Human resources rules prevent her from talking about specifics involving Flaherty and Interfaith, but she said, “I have a hard time trusting him based on past experiences.”

But even many of his most vocal critics have been unaware of the influence that he exerts as a campaign consultant behind the scenes. Astegos sometimes puts on events featuring prominent roles for the same people his consulting firm, Consult Idaho, is trying to elect. Donors who think they’re simply donating — or buying a raffle ticket — to help needy children may in fact be influencing local politics and helping bolster Flaherty’s profile.

Ted Silvester, vice president of marketing and development for the Marine Toys for Tots Foundation in Virginia, said the flyers in the school giveaway were likely inappropriate.

“They should not be doing that. We are an official activity of the Marine Corps,” Silvester told InvestigateWest. “You can’t be putting political materials in with the packages of the toys.”

Yet in Ada County, Idaho’s largest, the sheriff, prosecutor and two of three commissioners all hired Flaherty to run their campaigns in the last three years. As Flaherty has been elevated to more prominent positions — such as a seat on the local housing board — his powerful clients have become some of his most vociferous defenders.

Troubled past

Flaherty, a native Idahoan who studied finance at Boise State University, has always had big ambitions. In 2009, he later wrote on his website, he considered himself an entrepreneur — a loan officer with dreams of becoming a bank president. But that’s when he hatched a scheme: He made 31 separate $100,000 electronic fund transfers into an investment account. Even though his checking account had less than $1,300, he knew the investment bank would front him the money, giving him days to buy and sell more than $2 million before the scam was discovered. He was convicted of wire fraud and sentenced to 37 months in prison.

His website describes how “a lot of soul searching” during his stint in prison “altered the course of Tim’s life and he felt called to a life of service.”

To Flaherty’s supporters, this is a compelling part of his sales pitch — an ex-con turning a new leaf. Okhee Chang, a South Korean immigrant who pastors Living Word Church in Meridian, was nearly in tears as she described for InvestigateWest how Flaherty has helped supply the church’s small food pantry with food and other supplies.

“Everyone makes mistakes,” Chang said. “Tim has really tried to turn around and help people.”

In 2017, he launched Astegos, a nonprofit focused on street outreach, with dreams of providing a day shelter for homeless families. Ultimately, the mission shifted to running a warehouse for donated goods. It wasn’t just distributing toys for Toys for Tots, it also partnered with Good360, a national charity that sends truckloads of goods to nonprofits that online retailers aren’t able to restock. Astegos was given tons of items for free — everything from Stanley cups to Nike paraphernalia to unopened Amazon “Mystery Boxes” — and the right to distribute or sell them at deep discounts to other nonprofits.

As a business strategy, it appeared to work: Astegos’ net income last year reached $1.3 million. According to tax records, Flaherty’s Astegos salary climbed from $5,000 in 2017 to more than $83,000 in 2023.

Combined with Toys for Tots giveaways, Astegos allowed Flaherty to reinvent himself as a kind of Santa Claus — right down to delivering heaping bags of toys — and helped elevate him as an important figure in the Ada County nonprofit world. If nonprofits wanted cheap supplies, they could go to him for help.

But several people who work in that nonprofit community warn others not to trust Flaherty.

Lisa Veaudry and Kristy Ramirez told InvestigateWest they partnered with Flaherty while working for Stepping Stones, a nonprofit assisting renters in need. In 2017, they said he agreed to help them collect dozens of toys on a wishlist from kids in a low-income apartment complex in Boise.

“We stored all the toys in the office, and then he just wouldn’t give them up,” Veaudry said.

With barely 48 hours until the Christmas party for the kids, Veaudry and Ramirez said they were forced to scramble, putting out pleas on social media for donations in order to buy the toys for the apartment complex. A few days after that, Astegos — the company Flaherty had just started — was touting its own toy giveaways on social media.

“It was shitty,” Ramirez said about Flaherty’s behavior. “Unethical for sure.”

Other examples abound. AmeriCorps stopped sending volunteers to Astegos in 2022 because of volunteer complaints and worker injuries, according to BoiseDev reporting. A year earlier the Idaho Foodbank broke off its relationship with Astegos when, according to an email published in court records, Flaherty’s nonprofit missed a month of food deliveries that were supposed to go to low-income seniors.

When Flaherty applied for the Boise City/Ada County Housing Authorities’ volunteer board in 2022, some nonprofit leaders were alarmed. The housing agency manages low-income apartment complexes and a panoply of federal housing funds.

A program director with the Idaho Foodbank emailed the Housing Authorities to share that, after the food bank had tried to get Astegos back on track after its failure to deliver the food, Flaherty “threatened” the food bank’s “program and organization as a whole.”

Stephanie Day, director of CATCH, a Boise homeless services provider, wrote a fiery email, also contained in court records, to the director of the Housing Authorities’ board saying Flaherty gave her the impression of being a “textbook scam artist.”

She wrote that he’d mismanaged funds at Interfaith. She said he threatened to sue the city of Boise after it passed over a firm run by an Astegos board member for a software role that it was unqualified for. And she said Flaherty had been banned from submitting applications to a federal disability program after he’d allegedly been caught charging homeless people for assistance with the applications. She ended by saying that she couldn’t think of an experience with “him where dishonesty and abuse of taxpayer-funded programs were not a part of the process.”

Flaherty sued Day for defamation in 2023, but a judge tossed out the case after determining that Flaherty hadn’t properly disputed any “material fact” that Day had raised in her email and that he hadn’t actually shown the emails had damaged him.

At the October 2022 hearing where his appointment to the housing board was being considered, Ada County Commissioner Rod Beck said the commission had interviewed all the applicants “and found them all highly qualified.”

What Beck didn’t mention was that same month he paid Flaherty’s consulting firm nearly $14,000 for everything from campaign ads to social media help to food and refreshments.

Contacted by InvestigateWest, Beck, the former majority leader of the state Senate, scoffed at the idea that appointing his campaign consultant to the housing board could be considered a conflict of interest. He pressed InvestigateWest on whether the city of Boise or CATCH was secretly behind this story.

He said he hadn’t seen the email from Day before voting to put Flaherty on the board, but nothing he’s seen has shaken his faith in him.

“He’s just always been honest and straightforward,” Beck said. “I’ve never had any cause to question his judgment.”

Copperi, the Valley County sheriff, said he didn’t know about Flaherty’s conviction when he hired him to run his campaign — though he found out quickly. He said he does background checks on his deputies, not campaign consultants.

In fact, he first hired Flaherty because of his work with another member of law enforcement: Ada County Sheriff Matt Clifford.

Flaherty hadn’t just run Clifford’s campaign, he also donated $3,500 worth of in-kind contributions through Consult Idaho to Clifford’s Sheriff’s Cup golf tournaments — a political fundraiser — including Lego kits, Nike Golf swag, and an Amazon mystery box for tournament prizes. Clifford did not respond to interview requests from InvestigateWest.

While the word-of-mouth about Flaherty could sometimes be strikingly negative in the nonprofit world, the political world was a different story. Beck, for example, had hired Flaherty after seeing he sent out text messages for a state representative’s campaign.

Two out of three Ada County commissioners used Flaherty’s firm to run their campaigns; the third, Ryan Davidson, said he’d tried to hire Flaherty, too — but Flaherty turned him down.

Commissioner Tom Dayley paid more than $58,000 this election cycle to Consult Idaho for everything from yard signs to campaign literature to a small amount of robocalling.

Dayley said he saw no red flags with Flaherty. Asked if he knew about Flaherty’s felony conviction before hiring him, Dayley said, “I really don’t like answering these questions” and hung up the phone shortly after.

For Beaman, who ran against Copperi in the Valley County primary, Flaherty’s record alone was reason to question the judgment of anyone using him as a campaign consultant or placing him on a housing board.

“Why would you put somebody like that who’s had these issues with finances — and very intricate financial transactions to create these opportunities for himself — anywhere near housing or money?” Beaman asked.

‘This isn’t about you’

The national Toys for Tots Foundation has had its own experience with financial malfeasance. In 2000, the founder of the Toys for Tots Foundation was sent to prison for nearly five years after being convicted of diverting millions from the charity to pay for personal expenses. It took the nonprofit years to rebuild its reputation.

When a new Toys for Tots Foundation president came on in 2020, the mission grew. Toys for Tots had been known for its big Christmas giveaways, but it now expanded to doing year-round events, including “Unplug and Play” toy distribution events aimed at getting kids off of screens.

That meant relying less on the small local Toys for Tots organizations, and more on other local nonprofits or distributors like Astegos. Flaherty — or a local sheriff — could request a toy giveaway at a certain event, said Sgt. John Weems, Boise Toys for Tots coordinator, and Toys for Tots would typically make it happen.

“We just get told, ‘Hey, there’s an Unplug and Play event, do you have anyone who’s available to help?’ ” Weems said. He said Toys for Tots inventory is closely monitored, and that he hasn’t seen anything inappropriate from Flaherty since he started in September.

Staff Sgt. Jessieian Paala, the Marine who helped coordinate the Valley County giveaways before the May Republican primary, however, recalls recommending they go with a version of the flyer that included pictures of both local Marines and the sheriff on the back.

But when Paala showed up at one of the events, he saw they’d gone with an image focusing on the sheriff instead.

“Just a big-ass picture of Sheriff Copperi, that’s just kind of weird. Why is there a giant picture of you?” Paala recalled thinking. “This event isn’t about you.”

But ultimately, he told himself, he was there to hand out toys to kids, and that’s what mattered.

“I didn’t know there was an election coming up at all,” Paala said.

Tax-exempt 501c3 nonprofits like Astegos and Toys for Tots are legally prohibited from supporting or opposing candidates from public office, said Rick Cohen, spokesman for the National Council of Nonprofits. A “Thank you, Sheriff” flyer, however, is in a gray area.

“It sounds like they very carefully come up to the line between what’s OK and what’s not,” said Cohen, “but it’s not what a 501c3 is intended for. It’s there for the community, it’s not there for photo ops.”

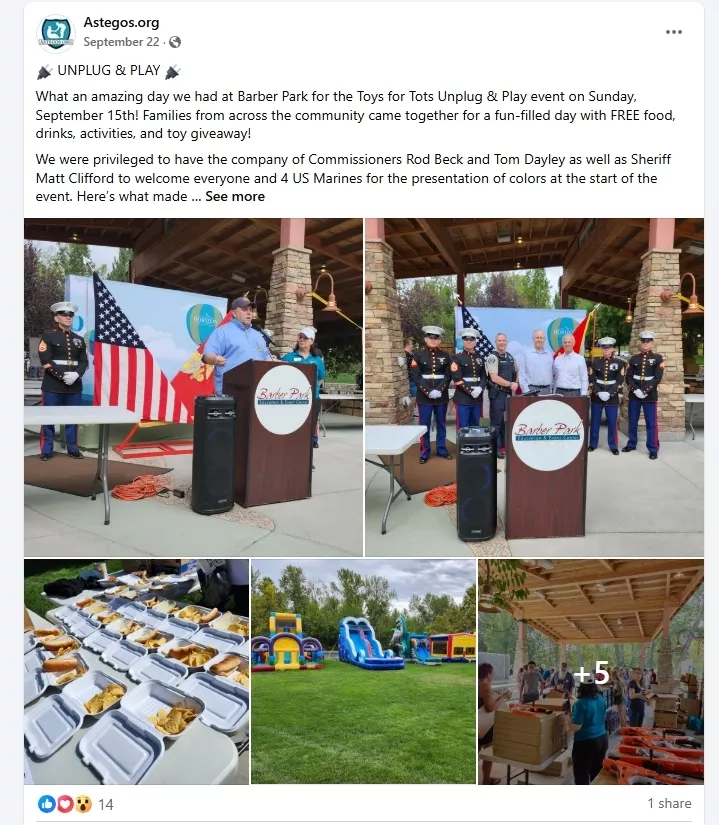

One week in September, Astegos passed out toys at a youth duathlon event, touting appearances by Ada County Commissioners Beck and Dayley, Sheriff Clifford, Prosecutor Jan Bennetts — all current or former clients of Flaherty’s political consulting firm who had the honors of handing out the LEGO prizes to the winners.

In another week that month, at Barber Park in Boise, Astegos gave away 14,000 toys to local children — and touted on Facebook that Clifford, Beck and Dayley were there to welcome the children. A post from the official Ada County Board of Commissioners page celebrated the toy giveaway and directed followers to Flaherty’s website.

Cohen said politicians show up at nonprofits all the time to get their picture taken to make it seem like they’re giving back to the community. But it’s messier when the nonprofit is run by the politicians’ campaign consultants.

“The issue here is an appearance of a conflict,” Cohen said.

Idaho’s conflict of interest rules require politicians to at least disclose if they are voting on a matter that could benefit a company in which they have a direct interest. But Dan Estes, spokesman for the Idaho Attorney General’s Office, said that restriction typically doesn’t apply when a politician is merely the client of a company that might be affected by a vote.

A politician appointing his campaign consultant to a housing board, in other words, doesn’t trigger Idaho’s conflict of interest rules, Estes said, unless, say, the firm cuts the politician a better deal in exchange for the appointment.

“It’s good that candidates for office want to give back,” Cohen said. “It’s probably best if they give back through a nonprofit that is not associated with the firm that is trying to get them elected. It doesn’t seem as genuine.”

The controversies that sometimes follow Flaherty can have other downsides. While Copperi said he plans to help Toys for Tots this Christmas, he was wary. Not because of anything he thought the organization did wrong, but because of the political backlash.

“I’ll be honest with you, I’ve hesitated to do anything with Toys for Tots after my competition brought this up. I don’t want to tarnish what Toys for Tots has done,” Copperi said. “Right now everything is kind of raw.”

Reporter Whitney Bryen contributed to this report.

The story you just read is only possible because readers like you support our mission to uncover truths that matter. If you value this reporting, help us continue producing high-impact investigations that drive real-world change. Your donation today ensures we can keep asking tough questions and bringing critical issues to light. Join us — because fearless, independent journalism depends on you!

— Jacob H. Fries, executive director

DonateCancel anytime.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters and never miss an investigation.