Free training: How to access police employment & misconduct data in the PNW

If you cover criminal justice in the Pacific Northwest — or want to — we’re hosting a free virtual training that may be useful to you and your newsroom

This is the first installment in a new InvestigateWest series called “Guarded by Predators,” exposing rape and abuse by Idaho’s prison guards and the system that shields them

In January 2018, a woman imprisoned at South Idaho Correctional Institution outside Boise was taken to a medical clinic to get abnormal cervical tissue removed. A guard named Ricardo Quiroz — known among inmates as “Corporal Q” — was her only escort, and he let her sit up front in a white van.

Afterward, still in pain and bleeding from the procedure, she and Quiroz walked back to the van. This time, she tells InvestigateWest, Quiroz told her to go all the way to the back. She complied. He followed her, telling her to take off her pants, says the woman, who asked to be referred to by her middle name, Lynn.

“There’s certain times where you fight, and there’s certain times that you don’t, and when you’re an inmate …,” Lynn trails off.

He raped her, Lynn says. Then he went back up to the driver’s seat and drove her back to prison.

Two years later, after Lynn got out of prison and away from Quiroz, she reported what happened. Investigators then discovered that just weeks before Quiroz drove Lynn to her medical procedure, he used his access to prison records to locate and contact a second woman who had recently been released from prison for a sexual encounter, police reports show.

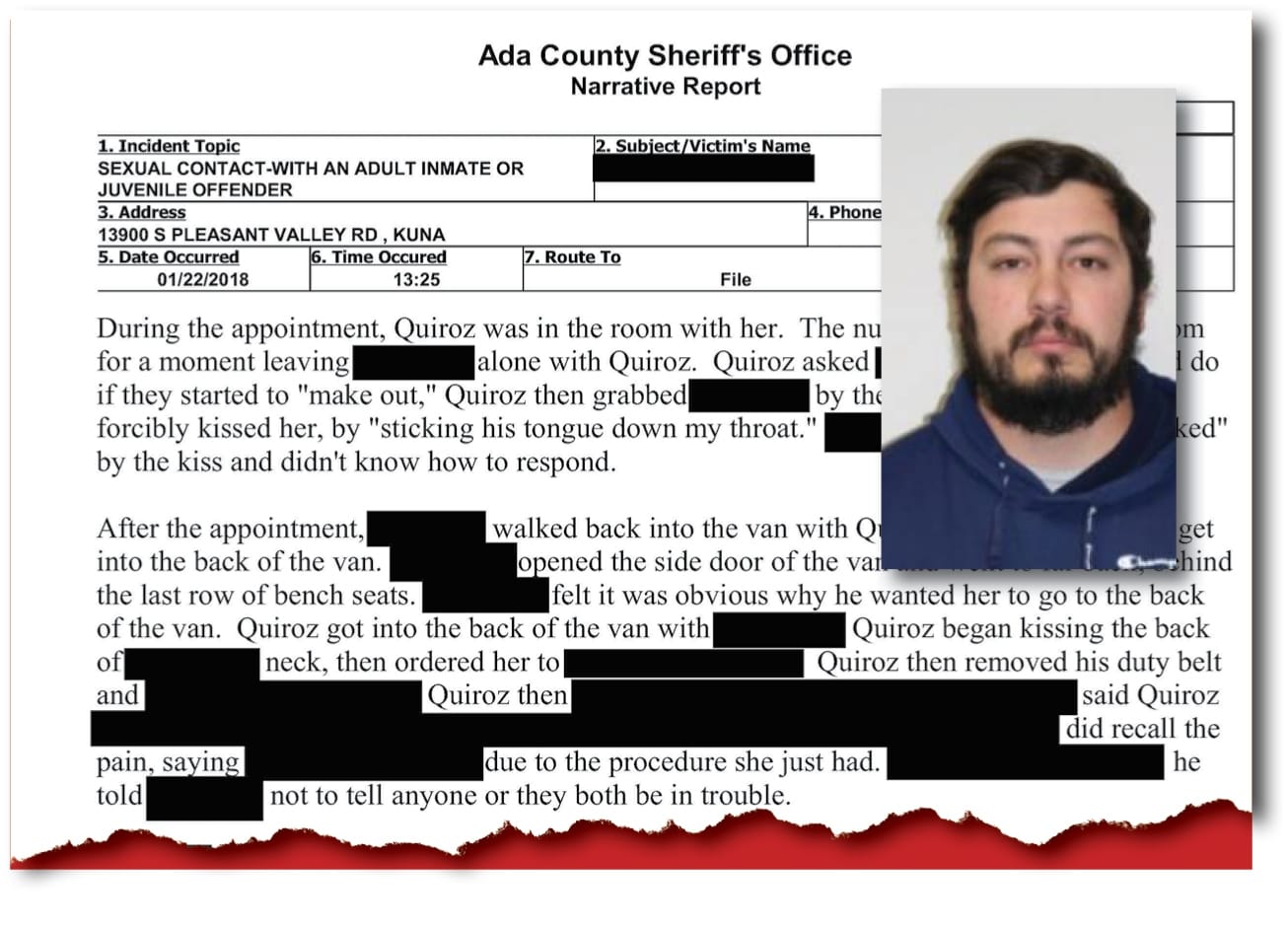

Ada County prosecutors declined to press charges for the second woman. But based on Lynn's report, they did charge Quiroz, now 34, with one count of sexual contact with a prisoner. He was convicted in 2021 of the felony, considered rape under Idaho law. He had to register as a sex offender and spend nine months in the custody of the Idaho Department of Correction.

Though such charges against an officer typically become major local news stories, Quiroz’s case received zero coverage — until now. Neither the Idaho Department of Correction nor the Ada County Sheriff’s Office, which investigated Quiroz, notified the public that a prison guard had been arrested for preying on a woman in his custody. To this day, four years since his conviction, both agencies have declined to release basic information about the crime that Quiroz pleaded guilty to.

InvestigateWest learned of the case after requesting from the Idaho court system all cases involving the charge of sexual contact with a prisoner since 2015. Reporters relied on a heavily redacted police report, audio of court hearings, and interviews with the victim and others aware of the case to produce this story, which reveals how the Idaho Department of Correction failed to prevent a guard from abusing vulnerable women he was tasked with keeping safe and then hid details from the public. The department declined to discuss the case with reporters for this story.

The case against Quiroz stands out as the only time in the last 10 years that an Idaho women’s prison guard has received a prison sentence for sexually assaulting an inmate. Most sexual abuse allegations, according to public reports compiled by the state prison system, are never referred to law enforcement by the Idaho Department of Correction — a likely violation of a federal law meant to stop prison sexual abuse. The cases that Idaho law enforcement does investigate rarely result in criminal charges, sometimes despite evidence that a guard had sexual contact with a prisoner, a felony whether or not the inmate is a willing participant in the moment. Even fewer guards are convicted of the crime if they are charged.

Although Quiroz is the rare exception, Lynn doesn’t see the case as a victory for sexual assault survivors. Instead, she calls it an “infuriating” example of why sexual abuse by guards is so common.

By 2018, Quiroz had built a reputation in his five years at South Idaho Correctional Institution, a 700-bed men’s and women’s prison. His supervisors described how Quiroz would “make a game of these sexual conquests with not only the inmates, but with other staff,” according to a statement made by Ada County prosecutor Katelyn Farley during his 2021 sentencing hearing. Farley declined an interview for this story. Quiroz did not return several messages seeking comment.

“He was making these decisions long before January of 2018. The sentencing material showed that he was engaged in inappropriate sexual relations since 2013. He was aware of these behaviors because it led to his divorce with his first wife,” Farley said in the hearing. The sentencing material she was referring to is not available for the public to obtain.

The “Guarded by Predators” series was fueled by women who shared their experiences behind bars and by prison workers who exposed systemic failures that allowed the abuse to occur. And we’re not done. If you have information, documents or a story to share, we want to hear from you.

The investigation of Quiroz focused on two alleged victims, one of them being Lynn. In police reports, the second alleged victim, whom InvestigateWest is not naming, described how when she was incarcerated at the prison’s prerelease center in late 2017, she would talk to “Q” — she didn’t know his real name — frequently about football. Eventually, he began flirting with her and rumors began to circulate within the prison, leading to internal investigations that hit dead ends, she said, because at that point, they hadn’t done anything physical. But she “enjoyed being treated like someone other than an inmate” and thought Q was attractive.

One day, she went into a janitor’s closet for cleaning supplies and he followed her in. Cameras could not see them. She told police that he tried to kiss her, but she turned her face away before rushing out when they heard voices.

A Department of Correction investigator interviewed her about the incident, but she “wasn’t honest with investigators” at the time, the police report says, “fearing her prison term would be extended for her involvement.” Q told her to look him up when she was released from prison.

Weeks later, in January 2018, she was out on probation and was living in a halfway house in Boise. She got an email that said “Its Me” as the subject — it was Q. Quiroz told her he looked her information up in internal department records, which the general public does not have access to, according to her account in a police report.

The two emailed back and forth, and they met up in his truck outside of her house. He was still in his uniform. The two began kissing, and Q put his hand on the back of her head, forcefully pushing it down toward his lap, according to the police report.

It is not clear exactly what happened after that. The Ada County Sheriff’s Office redacted from the police report all descriptions of sexual contact that Quiroz allegedly had with any women, despite “sexual contact with a prisoner” being the crime for which he was convicted.

In an email exchange included within the investigative file, the woman called Quiroz a “good kisser” and Quiroz replied to say she is too, “as well as everything (else) you did for me.”

The two stopped talking on Jan. 8, 2018, when she found out Quiroz had a girlfriend, the emails show. InvestigateWest was unable to reach the woman for comment.

Lynn, meanwhile, told InvestigateWest that Quiroz had been chatty with her during her time in the prison for drug possession. She’d heard rumors of “Q” having relationships with inmates, but she didn’t know if they were true. She thought he was a nice guy, and she trusted him to keep her safe during her medical appointment on Jan. 22, 2018.

Brenda Smith, director of the Project on Addressing Prison Rape at American University in Washington, D.C., said despite the safety risk, prison transports are often conducted by a single guard and provide an easy opportunity for sexual assault.

“It’s high risk and that has happened often,” Smith said. “That’s not something where somebody should go alone.”

Lynn considered reporting the assault to prison officials, but she thought it was too risky.

“Either you’re gonna make your time worse, or you might get lucky and somebody will believe you, and things will get better,” she said in an interview.

Though Lynn didn’t report the rape officially, she told another inmate what happened when she got back to the prison that night. That inmate later told police investigators that Lynn seemed scared of Quiroz after that and that Lynn had been in pain for several days afterward.

She got out of prison later that year, but in 2020 she was arrested again for a probation violation in north Idaho. The county jail asked her a series of standard questions while booking her, including whether she had been sexually assaulted by an officer. She told the truth.

“I was like, ‘OK, well, I know I’m going to get time, maybe they won’t send me to that prison,’” she said.

If you value this type of reporting, help us continue producing high-impact investigations that drive real-world change.

Support independent reportingQuiroz entered a guilty plea for the charge against him in November 2020. During the hearing, he admitted that he had sexual contact with Lynn and that the “whole allegation was true,” though no other victims were mentioned during the hearing.

But in his sentencing hearing a few months later, Farley, the prosecutor, noted that in the presentencing documents, Quiroz repeatedly used the word “consensual sex” when referring to what happened with Lynn. “This was in no way, shape or form ‘consensual sex,’” Farley said.

“(Lynn) paints a very different picture than what the defendant paints, and quite frankly it’s the more believable picture,” Farley said. “She discussed how that medical procedure was very painful, and she talked about how the defendant was forceful with her, that he demanded that she engage in this behavior.”

The prosecutor said the women in the prison may have been criminals, but they have also been through trauma, which is sometimes why they may turn to drugs to cope. Lynn, 33, says that was true of her. She grew up in Washington and 10 years ago was working toward a college degree, hoping to be a social worker working to keep families together. But she spiraled into depression and alcohol abuse, and soon after, she began using meth.

In some ways, prison is “the only safe place these women have” away from drugs, Farley said in the hearing. But that also leaves them extremely vulnerable.

“They can’t flee, they can’t get away. They feel as if they can’t resist, or their chances of freedom will be taken. And this defendant preyed upon those women. He used his position, his authority, and the power he had as a correctional officer to make these women sexual conquests,” Farley said.

Quiroz’s defense attorney, Joseph Filicetti, wrote Idaho’s sexual-contact-with-a-prisoner law in the ’90s — a fact he reminded the court of frequently during the case. He asked the judge only to impose probation, adding that he’s known Quiroz since he was an “amazing” kid, when Quiroz played soccer with Filicetti’s twins. He joined the U.S. Army as an infantryman, then came back from war to become a prison guard in 2013. Filicetti described Quiroz as someone deeply affected by his time in the military that caused post-traumatic stress disorder.

“When I saw him after he came back … he was a completely different kid. He was not social. He was very aggressive. When he came in and saw me on this case, my heart was broken for him because I could tell he really had done the things,” Filicetti said.

Quiroz’s dad testified in support of his son’s character. And then Quiroz himself spoke up, admitting he made “unethical decisions” and engaged in “reckless behavior” that he attributed to his mental health.

“I took my mental health for granted, and that caused me to fail as a human being. I am deeply sorry for all the pain I have caused everyone here today, the victims that are in this case, the disappointment I have brought to my family, my friends, my wife and my daughter.

“I will never hurt anyone again,” he said.

The judge, Patrick Miller, called Quiroz a “good kid who served our country in the military,” but called his conduct “extremely reprehensible” and “predatory.”

“We have to hold people who are in positions of power to a high standard,” Miller said.

He imposed a prison term of 10 years, with two years fixed. But Quiroz didn’t have to go to prison right away — instead, he first was to serve a “rider,” an alternative sentencing option in Idaho that offers defendants intensive rehabilitation in state custody, but away from the general prison population. If completed successfully, Quiroz wouldn’t have to serve his full term.

Only nine months into it, Quiroz had finished his rider successfully. Farley, noting that Quiroz “did a really good rider,” did not object to his release, and the judge adjusted the sentence. Quiroz now only had to get through probation.

Since 2021, only a few cases of sexual abuse charges against Idaho Department of Correction staff have made headlines. One guard at the Pocatello Women’s Correctional Center, Derek Stettler, took his own life in 2022 after he was charged with the same crime as Quiroz. A probation officer named Saif Sabah Hasan Al Anbagi fled the country after multiple women he supervised accused him of forcing them into sexual activity.

InvestigateWest has interviewed dozens of women who accused many more guards of sexual abuse, and reporters requested records that may document allegations of misconduct against more than 40 guards, including Quiroz. The department failed to provide records on all but two guards, and in some cases records clerks said they were not sure some of the guards ever worked for the department, even though other state records and victim accounts proved otherwise.

When asked why the Department of Correction did not notify the public or release records regarding its investigation into Quiroz or other guards, a spokesperson said in an email that the department does not release personnel records. The department declined to say whether it determined the allegations of sexual abuse against Quiroz were substantiated and why Quiroz was allowed to resign in June 2018.

Reporters also requested sexual misconduct cases that the Department of Correction referred to the Ada County Sheriff’s Office, which until 2022 was the agency that investigated most allegations of sexual abuse in Idaho’s prisons. The sheriff’s office asked InvestigateWest to pay more than $5,000 for 85 police reports, and added that they could not guarantee all those reports were relevant. The sheriff’s office, including its spokespeople, refused to work with reporters to narrow the request. The sheriff’s legal adviser Spencer Lay told InvestigateWest’s attorneys, who were working pro bono, that the office had information that could reduce the cost of the request but refused to provide it to reporters, saying it was “no longer available for free per Idaho code.” He added that the sheriff’s office “is not the research arm” of InvestigateWest.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters and never miss an investigation.

Idaho’s public records law allows agencies to waive fees if the information is in the public interest and the requester can’t pay the cost, but Lay denied a waiver, too, arguing it is “unclear” how allegations against publicly employed prison guards are in the public interest. InvestigateWest declined to pay the costs without assurance that doing so would result in Ada County providing the relevant documents without heavy-handed redactions.

InvestigateWest then asked for reports on Quiroz alone. Ada County Sheriff’s Office provided the reports, but redacted descriptions of the alleged crimes that it called “personal information” that “would constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.” Yet in some instances, the reports did not redact victim names or their medical information.

Lynn, released from prison for the last time shortly after Quiroz pleaded guilty, said she searched the internet for news coverage of the case. She wasn’t itching for the case to draw attention, but she was surprised to see none.

“Why not tell the public? It’s something the public should know, what’s happening in the prison system. And it’s something that needs to be changed,” she says. “There’s so many things that go on in those walls that people don’t even realize.”

It took years for Lynn to get her life back on track. She did two years of counseling before becoming a recovery coach, helping other people get through trauma. Today, she’s married and has a daughter.

“For the longest time, I felt like I was still in my own prison, and I felt like I couldn’t trust men, obviously, like it wasn’t just that situation, but that one definitely increased it, because it was one of those situations that I couldn’t just leave where I was at. I was stuck there,” she says.

She listened to the hearings in the case for the first time this year, when provided by InvestigateWest. Despite what he did, she felt some sympathy and forgiveness for Quiroz, knowing he was going through his own mental health battle.

“At least I can see him now as a person,” she says.

Still, she worries that the leniency that the prison system and the courts gave Quiroz only made it more likely other women will be abused.

“If that’s what one deputy gets for taking advantage of his position where he’s supposed to keep people safe,” she says, “then why wouldn’t other deputies do that and have little to no consequences?”

This reporting was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the Pulitzer Center.

The story you just read is only possible because readers like you support our mission to uncover truths that matter. If you value this reporting, help us continue producing high-impact investigations that drive real-world change. Your donation today ensures we can keep asking tough questions and bringing critical issues to light. Join us — because fearless, independent journalism depends on you!

— Jacob H. Fries, executive director

DonateCancel anytime.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters and never miss an investigation.