Two Colville women were booked into a rural Washington jail. It became a death sentence

Critics say WA jails are letting opioid users suffer from withdrawals, leading to preventable deaths

A decade before Will Smith forever linked professional football with traumatic brain injuries in the movie “Concussion,” three tragic stories on much smaller stages proved to the nation how dangerous concussions could be.

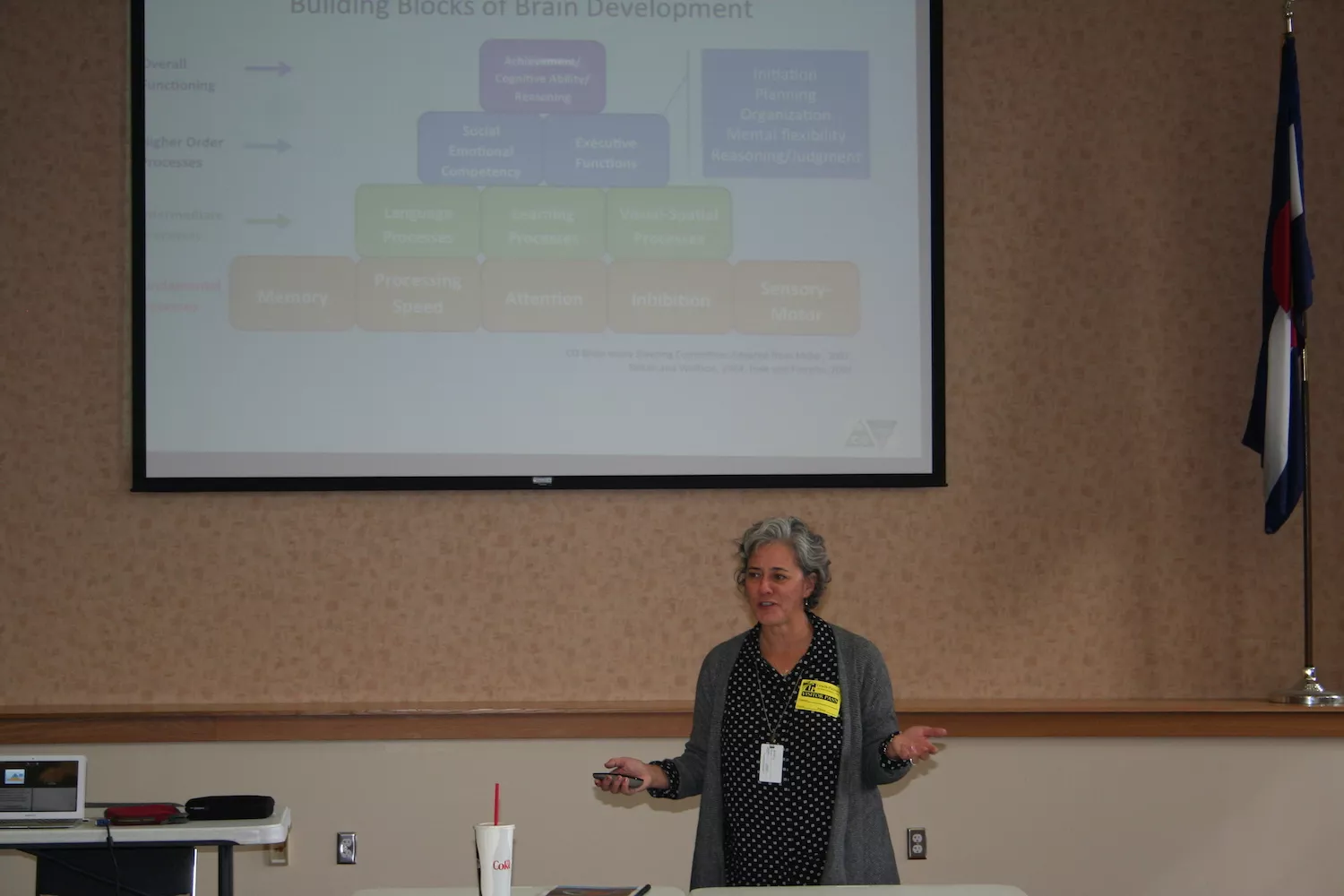

“Zackery. Max. Jake. It turned into this whole movement,” said Dr. Karen McAvoy, a Colorado brain injury expert.

She was referring to a trio of concussed high school football players — including Oregon’s Max Conradt — who put names and faces on a problem that had been largely ignored for decades.

Their painful stories resulted in legislation that has protected youth across the continent by establishing best practices for safely easing rattled student athletes back to competition.

What’s been missing, according to some education advocates, is an equal focus on how to help all kids with brain injuries succeed in the classroom.

What is BrainSTEPS?

Click here to read about Pennsylvania's brain injury education program, BrainSTEPS, which presents a modular way for school staff to think about brain injuries and disorders of all types. Trainings such as these help make it possible for teachers to feel confident managing concussion recovery as students return to the classroom.

Conradt and Washington’s Zackery Lystedt suffered serious permanent brain injuries — in 2001 and 2006, respectively — after taking second hits on the football field. Colorado’s Jake Snakenberg, whom McAvoy knew personally, died in 2004 from the same circumstances, known as second-impact syndrome.

In response to the tragedies, state legislatures — led by Oregon and Washington in 2009 — began to pass return-to-play laws. These are rules that require concussed athletes to be pulled from practice or competition and govern when they can safely return to sports in order to ward off potentially catastrophic damage.

“That is the premise of all concussion management laws,” McAvoy said.

Most legislation didn’t touch the impact of concussions on non-athletes, nor to schools’ primary mission: learning.

“It just never even crossed people’s minds in the beginning,” McAvoy said. “That educator piece was foreign to other people’s thinking.”

Concussions not only from sports

McAvoy, who had worked in brain health for years before meeting Snakenberg, wondered whether the attention to this more common injury would finally open the door to school-based approaches needed for all brain injuries and disorders.

So far, that hasn’t happened.

As detailed in an earlier story of this series, McAvoy developed a program called REAP to teach school staff, families and medical personnel how to work together as a team to address a concussed child. It builds on characteristics and techniques that are common to all students with brain injuries or disorders. (See, “Colorado's concussion approach combines education, medicine, a team approach,” Jan. 15, 2019)

“The athletics is where it gets a lot of attention, but honestly that’s not where the most head injuries occur,” McAvoy said.

Journalists working on our Rattled: Oregon’s Concussion Discussion series heard from many readers about youth concussions suffered outside of school sports: on bike trails, backyard trampolines and in car accidents.

“I’ve had two kids have a concussion falling into a dresser in their home,” said Dr. Becca Carl at Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

Brenda Eagan-Johnson, who leads Pennsylvania’s 300 brain injury education consultants, has found in her state’s referrals to special education that about half of all concussions in school-age children are not from sports.

“There’s always those locker concussions. Bus concussions. Local fair rides that cause concussions. Snowball concussions. Sled-riding concussions,” Eagan-Johnson said. “We’ve just had them all.”

Return-to-play legislation, which has the force of law and the threat of sanctions, has been effective in moving districts to pay more attention to athletics concussions. But the philosophy for concussion management in the academic world has been to simply offer educators resources and hope they adopt them effectively, if at all.

That approach has had mixed results.

Different approaches

Oregon, Colorado and Pennsylvania are similar in that they operate on a local-control model of education — school districts can decide whether they want to take advantage of educational models and resources, like concussion management.

What science says about concussions in schools

• Concussed students have trouble concentrating, have low energy, have difficulty remembering information and just don’t process very well. They could have sensory symptoms like nausea or an aversion to bright lights.

• Concussed students benefit from light amounts of cardiovascular exercise — like walking from class to class. Even if the child still has a headache or other mild symptoms, there is no need to stay home in a dark room. “That’s really been debunked,” says Dr. Becca Carl at Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

• Supports in school could mean forgiven assignments and skipping nonessential tests. Pushing off all the work until a vacation or waiting until the student is “better” ramps up stress as work piles up — which makes recovery longer.

• 70 percent of concussed youth get better in four weeks or less. Only a small percentage will need long-term care.

• Legal academic accommodations like 504 plans and Individual Education Programs are usually overkill and often too slow to implement for most students with concussions.

• Educators and parents need to direct the supports. Concussion symptoms change from day to day and can resolve rapidly. There’s no time to keep going back to the doctor for updated medical restrictions.

• Concussions have psychological effects. How we react to them can, too. Stress related to being out of school, away from the game, being taunted by peers, or even overprotected are all ways that concussion symptoms could last longer or lead to secondary problems.

And, McAvoy says, too many still don’t.

“There is still a lot of myth and misunderstanding that if you have an athletic trainer, you have concussion management. We need to think wider,” McAvoy says. “That is exactly what the problem is, is that so far this whole world of concussion has been about sports and school-sponsored sports.”

Colorado, Pennsylvania and several other states have gone with REAP — a model McAvoy developed and released relatively quickly. During the 10 years it has been out in the world, it has gotten widely positive reviews, though McAvoy has no hard data on its effectiveness.

Because it has been freely available, there’s no way to know how many educators have been trained in REAP, but it is easily in the thousands. In Colorado, its Department of Education also has two staffers who continually coach school districts on how to approach traumatic brain injuries, including mild ones like concussions.

Pennsylvania’s Eagan-Johnson, who worked with McAvoy to develop the return-to-learn module Get Schooled on Concussions, probably has been more effective than anyone in the country at training people on school-based concussion management.

“No one is mandated to do it, but so far we’ve trained over 2,000 school teams. And I know no other state has done that,” she said.

Eagan-Johnson credits a few lawsuits in her state with raising awareness of the issue and encouraging school administrators to take advantage of her trainings.

In Oregon, the Department of Education pays the Center for Brain Injury Research and Training to manage its traumatic brain injury teams, including concussion management education.

To address concussions in schools, CBIRT spent years and $600,000 developing a 10-hour online professional development course called “In the Classroom After Concussion.” Only 141 people have taken the course so far. Most of them have been members of CBIRT’s school-based teams.

Now that clinical trials of “In the Classroom” have finished and it’s proven to be an effective training device, CBIRT Director Ann Lang hopes to market the course more broadly.

Iowa Brain Injury Alliance CEO Geoffrey Lauer said his state was among the 10 that have chosen over the years to go with Colorado’s model. But Lauer said he believes either REAP or “In the Classroom” are good approaches.

“The ‘right’ way to do it or the ‘best’ way to do it, it kind of depends on how you see the world,” Lauer said. But, he added, schools should pick something and do it. “Not attending to this is resulting in literally thousands of students having socioeconomic trajectories that they didn’t need to have.”

Rattled: Oregon’s Concussion Discussion is a joint project of InvestigateWest, the Pamplin Media Group and the Agora Journalism Center, made possible in part by grants from Meyer Memorial Trust and the Center for Cooperative Media. Researcher Mark G. Harmon from the Portland State University Criminology & Criminal Justice Department provides statistical review and analysis. The New York-based Solutions Journalism Network provided training in solutions-based techniques and support to participating journalists.

The story you just read is only possible because readers like you support our mission to uncover truths that matter. If you value this reporting, help us continue producing high-impact investigations that drive real-world change. Your donation today ensures we can keep asking tough questions and bringing critical issues to light. Join us — because fearless, independent journalism depends on you!

— Jacob H. Fries, executive director

DonateCancel anytime.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters and never miss an investigation.