Free training: How to access police employment & misconduct data in the PNW

If you cover criminal justice in the Pacific Northwest — or want to — we’re hosting a free virtual training that may be useful to you and your newsroom

InvestigateWest reporting exposes sexual abuse by guards, retaliation against victims and a system that fails to track the scope of the problem

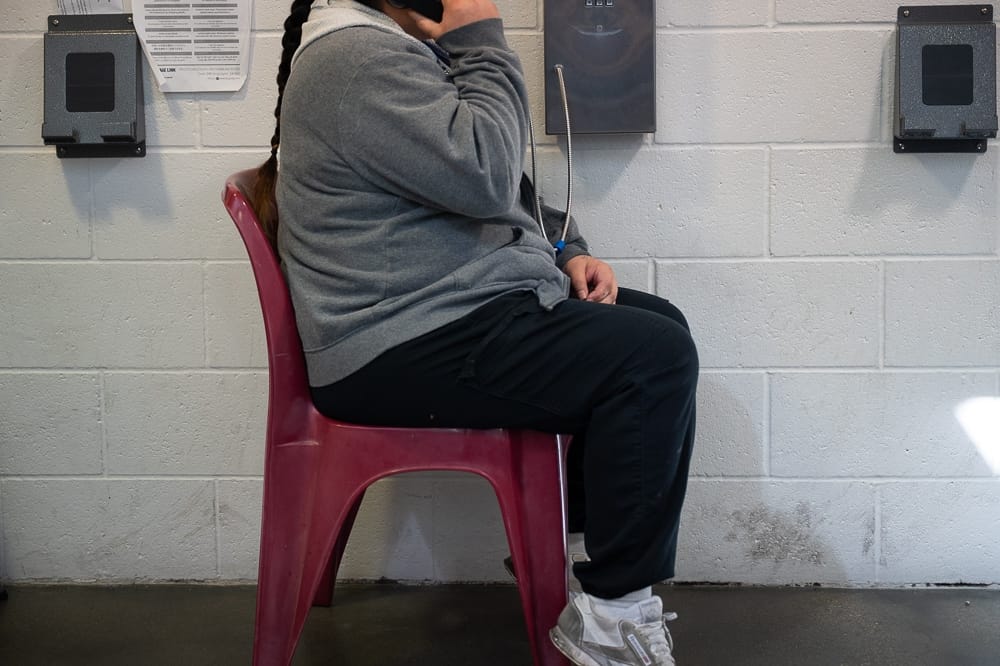

In Idaho prisons, more than two dozen women say guards prey on them with little fear of consequences — and those who speak up are often punished.

Their accounts, gathered over an almost yearlong investigation, reveal the chilling reality of incarceration in a state that locks up women at the nation’s highest rate.

Since 2020, there have been at least 59 documented allegations of staff sexually abusing imprisoned women, InvestigateWest has found. That number, which totals allegations recorded by several agencies, represents the most thorough accounting of sexual abuse in Idaho women’s prisons to date. But it remains an undercount of the problem. Reporters interviewed 25 women who said they experienced sexual abuse across Idaho’s three women’s prisons, many of whom did not report the abuse at the time for fear of retaliation.

To verify their claims, InvestigateWest interviewed witnesses, former employees and whistleblowers; pored through thousands of pages of court records, Department of Correction reports and investigative files; and listened to hours of interviews conducted by department investigators and law enforcement.

In the coming days, InvestigateWest will publish examinations of how these cases are handled by the prison system, police and courts in Idaho, with detailed accounts from survivors of sexual abuse.

And it will explain how prison officers are able to avoid consequences when they’re accused of sexually abusing inmates under their control. InvestigateWest reporters found:

Julie Abbate, an attorney who spent years investigating sexual abuse in women’s prisons for the U.S. Department of Justice and helped write the standards of the Prison Rape Elimination Act, said InvestigateWest’s findings indicate “a really, really troubled culture” for the roughly 1,300 women imprisoned in the state.

“Those numbers are really a lot. It indicates a huge problem,” Abbate said, noting that accused workers typically have abused more than one inmate.

She added that it’s “super telling” that 18 workers resigned shortly after misconduct was reported. “Folks don’t tend to resign if there’s not something there.”

The findings reveal a systemic failure to stop sexual abuse in prisons a decade after Idaho announced it would adopt the federal standards of the Prison Rape Elimination Act, signed into law in 2003 by President George W. Bush. When Idaho announced it would comply with the law in 2015, it was one of only four states that hadn’t yet.

Department of Correction Director Bree Derrick said the number of allegations identified by InvestigateWest “don’t look good,” but she disputed that there is a culture of letting guards off the hook for sexual abuse and retaliating against inmates who report it.

“I don’t think that’s true. I think that's painting with a very broad brush,” Derrick said. “I don't want to dismiss that this could have been several women's experience. Of course if that’s the case, we want to do better in that space, in terms of holding our staff accountable and making sure they pay a price for that, and making sure that the women are not in a place where they’re being retaliated against.”

The “Guarded by Predators” series was fueled by women who shared their experiences behind bars and by prison workers who exposed systemic failures that allowed the abuse to occur. And we’re not done. If you have information, documents or a story to share, we want to hear from you.

The federal law considers any sexual contact between a prison worker and an inmate to be sexual abuse, even if the inmate is willing in the moment, and it calls for any potential criminal abuse or harassment to be investigated by law enforcement.

Derrick, who spent six years as deputy director until she was promoted in April, said the Idaho Department of Correction “has a decent track record” of complying with the Prison Rape Elimination Act, pointing to the fact that each prison has successfully passed their audits.

InvestigateWest’s review of the audits and annual reports, however, found inconsistencies and violations of the federal standards. Allegations of sexual abuse in Idaho prisons are commonly not investigated by law enforcement, as the federal standards call for, but instead by the Idaho Department of Correction, which has kept most allegations hidden from the public. The department, in a statement, did not deny that some reports of staff sexual abuse only receive an “administrative review,” adding that “not all cases rise to criminal investigations.”

Additionally, in order to receive federal funding for following the federal law, states must implement standards and training on how to recognize and respond to sexual assault and track allegations. No one at the Department of Correction was able to tell InvestigateWest how many sexual misconduct complaints had been filed against prison staff.

The Department of Correction provided only 24 cases when reporters asked for all sexual misconduct complaints against women’s prison workers in the last five years — a number that conflicts with the department’s own count in its annual reports mandated under the Prison Rape Elimination Act. After reporters asked about the discrepancy, the department provided a new list of reports, which still did not match the annual reporting data. Through police and court records, InvestigateWest identified more cases that had in fact been documented by the Department of Correction, but the department either could not find those records or withheld them from reporters.

“If those allegations, those numbers, were put out by the department, they should absolutely, without question, have the corresponding files of the reports … and any other files that would be related to that PREA report that they turn over to the auditor when the auditor goes on site,” said Abbate, who is a certified federal auditor.

The federal law is relatively toothless, however, and many of its requirements go unenforced. The consequences of noncompliance are minimal: States would lose 5% of federal grants used for prison purposes. When Idaho was not complying with the federal law before 2015, that amounted to $82,000 lost per year.

Victims said they had little incentive to report when they were abused. An investigation by prison staff can mean that victims get moved away from fellow inmates and into restrictive housing for their safety. Many women described that as the “hole” — small cells where prisoners are confined up to 23 hours a day like a maximum-security prison. When word spread that they had spoken up, victims said they were blamed by other inmates and staff who widely assumed the victims were initiating relationships with guards in exchange for special favors or contraband.

Security camera blind spots make it easier for prison staff to get away with abuse. Since 2006, inmates were raped in closets, at work sites, in a break room and in employee offices without cameras, records and accounts from dozens of former inmates and officers reveal.

Some Department of Correction policies call for guards to be alone with inmates. When inmates are disciplined for violating a rule, they are subject to a hearing where they can dispute the allegation. But those hearings are conducted behind closed doors, out of sight of security cameras, usually by a single sergeant with no other witnesses. State policy does not require video of the hearings, only an audio recording that the sergeant can turn off or on as they see fit. Multiple women told InvestigateWest that officers used these hearings to offer lenient discipline in exchange for sexual favors. The Department of Correction said it was only aware of “one complaint of this nature,” but that “after investigation, the allegation was not sustained.”

Help InvestigateWest's reporters hold power accountable across the Pacific Northwest.

Join usWhen abuse has been reported, some allegations were quickly dismissed by prison officials, who operate with little oversight from department leadership. Wardens at each women’s prison rejected warnings of suspected relationships between inmates and guards, and failed to initiate timely investigations, records show.

Pocatello Women’s Correctional Center Warden Janell Clement signed off on three reports submitted by a staff member describing a guard rumored to be in a relationship with an inmate, yet none of those reports triggered a formal investigation. An investigation launched the following year revealed the kitchen guard had raped one inmate and abused or harassed others. The Department of Correction declined to answer questions regarding the case and would not allow InvestigateWest to interview Clement.

At South Boise Women's Correctional Center, Warden Nick Baird interrupted a meeting with one of his staff to play her a recording — a sexually explicit phone call between an inmate and a former guard. Baird played the recording for food service supervisor Robin Spackman at least four times telling her that he “gets bored” and “thinks it’s funny,” according to a lawsuit later filed by Spackman. The recording was evidence obtained during an investigation into the alleged guard, who was allowed to resign and relinquished his officer certification. Records give no indication that prison officials referred the case to police. The allegation was not investigated by law enforcement, according to police records.

The Department of Correction spokesperson, when asked about this, said in an email that the department had “completed an investigation into the Johnathan (sic) Nance matter,” referring to the kitchen guard Jonathan Nance, but declined to share the result, adding, “the department denies all accusations by Ms. Spackman.” Nance did not respond to messages from InvestigateWest.

In the instances in which the Department of Correction referred abuse of inmates by staff to police, case files reviewed by InvestigateWest reveal shoddy investigations in which detectives ignored leads that could back up the women’s allegations. In one case, Idaho State Police detectives interviewed a suspect for a mere nine minutes and never directly asked the guard if he had sexual contact with the inmate, who accused him of raping her multiple times. The detectives then told the suspect that they hoped instead to go after women for filing false reports.

A state police spokesperson declined requests to interview the detectives and refused to answer specific questions about the investigation.

Evidence of sexual abuse or harassment by prison workers often still isn’t enough for a conviction in Idaho, a review of court records and investigative files shows. Idaho laws fall short of the federal standards that prohibit sex, groping, fondling, gawking and even suggestive comments by prison workers, making it difficult for prosecutors to hold abusive guards accountable.

The findings give a peek into what experts say is happening in state and federal prisons nationwide. Fara Gold, a longtime state and federal prosecutor who wrote the U.S. Department of Justice guide for prosecuting violence against women, said prisoners are vulnerable to being sexually assaulted because criminals aren’t seen as credible.

“If you’re in custody, who do you tell? You’ve been prosecuted by law enforcement, you’re now potentially sexually assaulted by law enforcement. Who’s going to believe you?” Gold said. “They are targeted, these victims, because the perpetrators know that no one’s going to believe them.”

This reporting was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the Pulitzer Center.

The story you just read is only possible because readers like you support our mission to uncover truths that matter. If you value this reporting, help us continue producing high-impact investigations that drive real-world change. Your donation today ensures we can keep asking tough questions and bringing critical issues to light. Join us — because fearless, independent journalism depends on you!

— Jacob H. Fries, executive director

DonateCancel anytime.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters and never miss an investigation.