Two Colville women were booked into a rural Washington jail. It became a death sentence

Critics say WA jails are letting opioid users suffer from withdrawals, leading to preventable deaths

While some counties are devoting money to track down guns, others rely on the honor system to ensure firearms are turned over

In July 2024, Joseph Leitz walked into a red brick sheriff’s office building in the small Western Washington city of Shelton and turned in two handguns.

A court commissioner had ordered Leitz to do so after his then wife, Lauryn Berg, secured a domestic violence protection order, alleging he had beaten and raped her, threatened to take their kids, and held an unloaded gun to his head, pulling the trigger three times. Leitz denies the allegations.

The commissioner later determined that Leitz no longer possessed any firearms, based on Leitz’s word and documentation from the Mason County Sheriff’s Office. But Berg believed her ex-husband still had nearly a dozen other firearms, including an AR-style semi-automatic shotgun that he stored in a safe during their 12-year relationship.

“I’ve seen them. I’ve shot them. I have videos of my friend shooting them,” said Berg, referred to here by her maiden name. “When they said ‘handguns,’ I was like, ‘Are you kidding me?’”

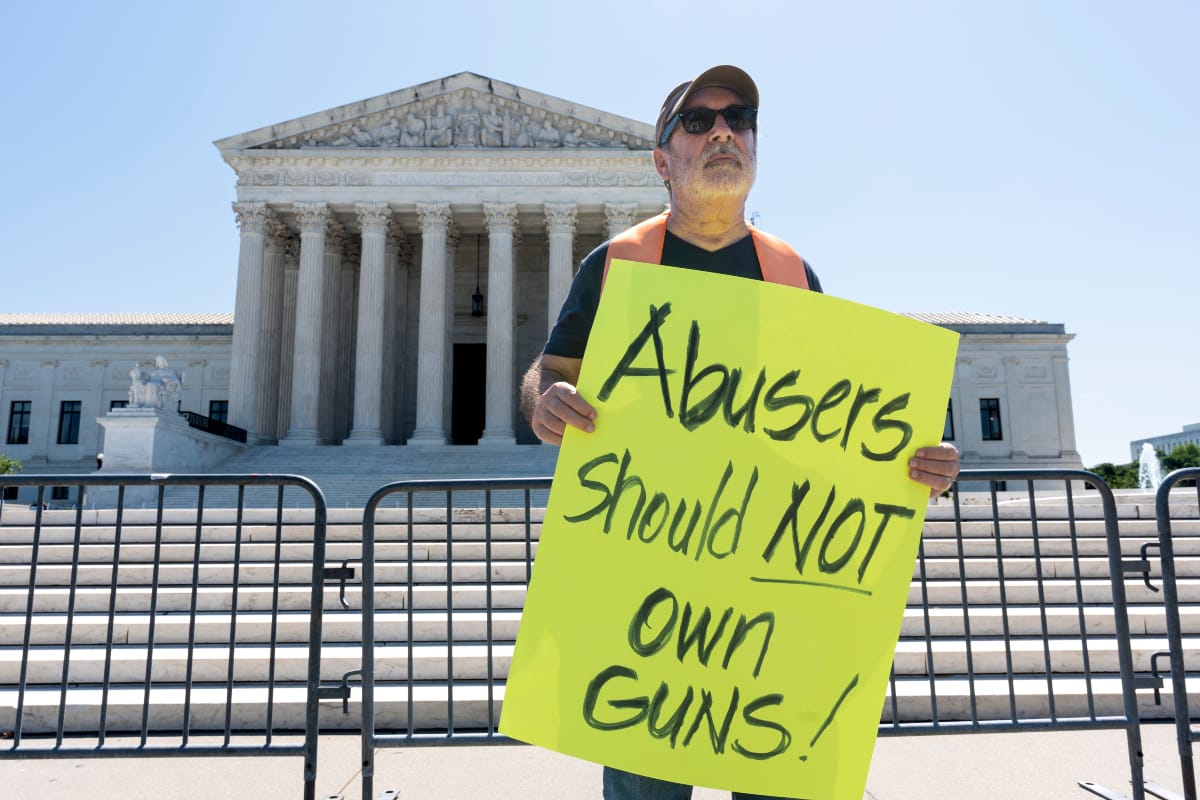

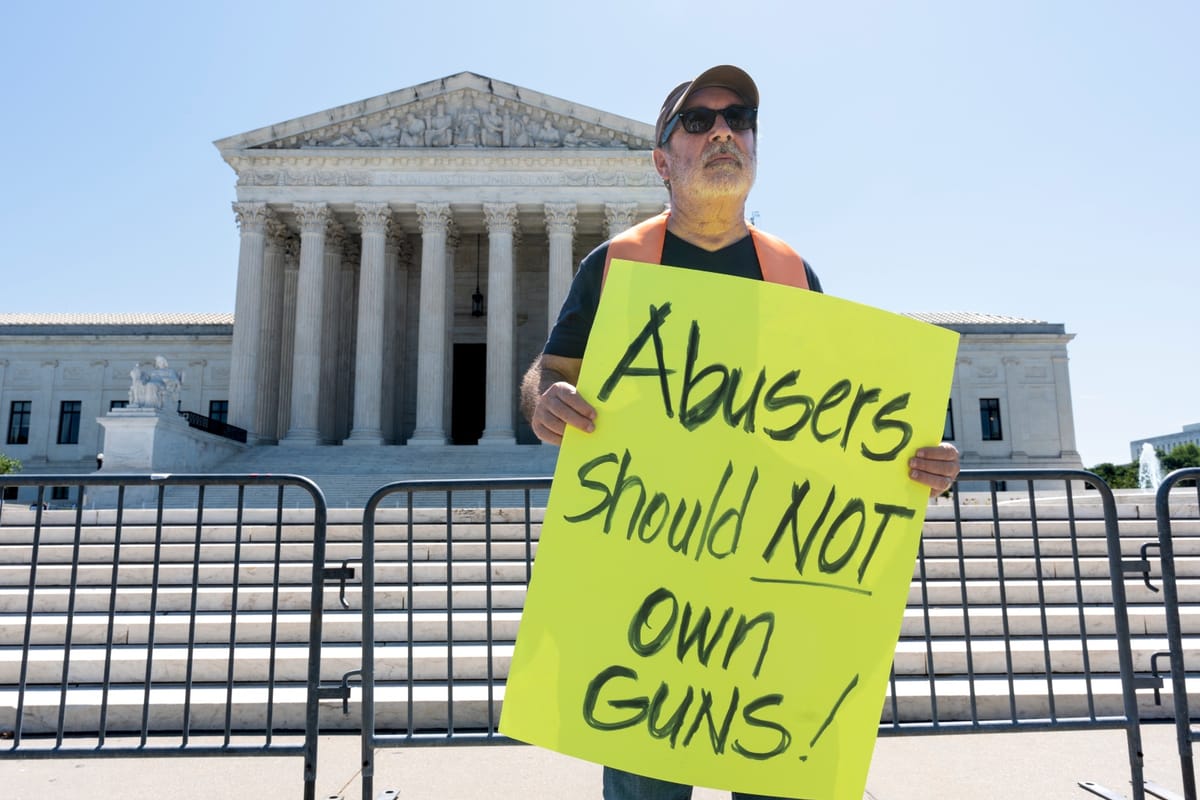

Washington, with some of the nation’s strongest civil protections for domestic violence survivors, is one of 22 states that require certain alleged abusers to turn in their guns while under a restraining order. But researchers say even with these laws in place, most states lack mechanisms to actually ensure accused abusers are disarmed, which has been shown to lower rates of intimate partner homicides.

Despite Washington’s pioneering policies, Berg’s fears that her ex could still have access to firearms show the holes in the state’s system for enforcing surrender orders. While some communities, like King County, have invested substantial resources into the problem and are touted by gun violence prevention advocates as a model, many jurisdictions still rely primarily on the honor system to ensure guns are turned in. Judicial officers waive or give cursory attention to hearings that would give survivors an opportunity to present evidence of missing guns, according to firearm enforcement advocates and attorneys. And even when there are indications that a person is violating a surrender order, some police and prosecutors are hesitant to investigate over concerns of infringing on an alleged abuser’s constitutional rights.

As a result, whether a survivor will actually see their abuser’s firearms confiscated in Washington depends heavily on where they live — and what their local courts, police or prosecutors think of the law.

“We’re going basically on the stance that they’re providing true and actual factual information to us,” said Stephen Rowe, a sergeant at the Mason County Sheriff’s Office, where Leitz was ordered to surrender his guns. “Whenever you have a case that challenges the Constitution, they’re difficult to enforce.”

Washington state Rep. Lauren Davis, who has sponsored several bills to protect domestic violence survivors, said that although other states might look to Washington as an example, she “wouldn’t give us any gold stars.”

“It says all of these things on paper, but it’s not actually happening,” Davis said. “Not every judge is going to take a victim’s word seriously. Not every prosecutor is going to bother litigating that with the court, even upon the victim’s word. And not every court even has a compliance hearing in the first place.”

This patchwork enforcement leaves survivors like Berg with a very real fear that their alleged abusers could act on threats of gun violence. More than 70 women are shot and killed by an intimate partner every month on average in the U.S., according to the national gun violence prevention organization Everytown for Gun Safety. In Washington, two-thirds of the state’s 43 domestic violence-related homicides reported in 2022 were by firearm, research shows.

Many accused abusers tell police and courts that they don’t have any guns, even when that’s not the case, firearm-surrender enforcement experts say. In Kitsap County, where Berg’s case is, the Superior Court issued orders to surrender weapons in 1,961 civil protection order cases from 2022 to mid-August 2025, according to data provided by the county clerk’s office. Only 12% of those individuals turned over their weapons and submitted the required receipt from law enforcement to the court, according to a data analysis by the Gun Violence Data Hub, a data initiative by The Trace, a nonprofit newsroom covering gun violence in the United States. The majority — 56% or 1,094 people — simply claimed that they didn’t have any guns to surrender, although at least 12 of those people refused to sign a court declaration swearing to that.

Leitz, a 34-year-old truck driver, told InvestigateWest that he did have an AR-style shotgun and other guns during his marriage, but gave them to his dad and cousins before being hit with the surrender order. While that’s allowable under state law, the sheriff’s office and court never attempted to verify his claim, according to court and police records.

Although Leitz says he can’t access the guns, Berg doesn’t feel safe knowing that his family members have them.

“He could go get them at any time,” she said.

Government funding is making a difference in some communities, showing what can be done when counties have dedicated money and a commitment to enforcing the orders. King County’s domestic violence firearms enforcement unit, made up of police, prosecutors, advocates and enforcement experts, tracks down evidence of missing firearms and encourages alleged abusers to turn them in — sometimes leading courts to resort to jail time and fines for those who still don’t comply.

Spokane, in Eastern Washington, has also sharply increased its collection by thousands of guns since 2019, when it began receiving federal dollars to prioritize the issue, according to data provided by Spokane’s YWCA, which is working with local police to address the issue. But amid the Trump administration’s threats to shrink the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office on Violence Against Women and slash funding for domestic violence services, it’s not clear if the federal funding will be available in the future.

Increased funding, however, is only one piece of the puzzle, according to researchers and victim advocates. It also takes a coordinated effort by police, prosecutors and courts to prioritize the issue.

“Resources are always brought up as a challenge, and I totally understand that,” said Renée Hopkins, CEO of the Alliance for Gun Responsibility, a Washington nonprofit that recently launched an online portal to help survivors navigate the state’s civil protection order system. “My response to that is, we’re talking about some of the highest risk situations. Some of it has to come down to priority.”

When an alleged domestic abuser is ordered to surrender guns in Washington, state law lays out specific steps to ensure that all firearms are accounted for. Police serving the order must tell them to immediately turn in their guns and seize any firearms “in plain sight” or discovered through a lawful search. The alleged abuser must sign a declaration that they have no guns, or provide evidence, like a receipt from police, that the weapons are no longer in their possession. The court then reviews this evidence in a hearing to determine whether all guns have been surrendered.

The process is straightforward in theory. But people lie.

“The declaration of nonsurrender that’s signed in court, almost always they’re not accurate. They’re not being honest,” said Amie Simeral, a domestic violence firearms analyst at the Spokane YWCA, which provides resources for survivors.

Yet many Washington communities still rely largely on the accused abuser’s word. In Yakima, a city in rural central Washington with high rates of gun ownership and domestic violence, there’s “not a whole lot” that police can do to ensure people are telling the truth, said Yakima Police Department Capt. Chad Janis.

Yakima is one of 12 pilot sites nationwide that receives federal funding from the Office on Violence Against Women to protect survivors from gun violence. Yakima’s $500,000 grant goes toward costs like data collection, equipment for police to send protection orders electronically, and a coordinator to help monitor and encourage firearm surrenders.

But even with this increased support, tracking guns remains overwhelming. Like Berg’s ex-husband, many accused abusers give their guns to relatives or friends just before an order is served, said Janis and Mason County Sheriff’s Office Sgt. Rowe.

“The law allows that. And there’s really no verification process,” Janis said.

Following up with family members takes a lot of manpower, Rowe said. “And I will tell you, most agencies are short-manned.”

Still, there are steps that police and courts should take, according to enforcement experts and attorneys. In King County, judges ask family members and friends for a sworn statement confirming they were given guns.

“But after that, I don’t know if there’s much more that can be done,” said Karla Carlisle, a managing attorney with the Northwest Justice Project, a nonprofit legal aid program in Washington. “Obviously, the big elephant in the room is, what’s stopping the family member from just handing over the guns?”

Constitutional challenges have also hampered the implementation of Washington’s firearm surrender law ever since its passage in 2014, though recent court rulings have affirmed its constitutionality.

Some judicial officers who stopped issuing surrender orders in 2023 over concerns that they infringe on accused abusers’ protections against self-incrimination and unreasonable search and seizure have once again started ordering them, following a state Court of Appeals ruling in June.

In 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court also put an end to Second Amendment concerns when it affirmed the constitutionality of a federal law prohibiting people subject to domestic violence restraining orders from possessing firearms.

Yet when it comes to actually removing these guns, some police officers remain wary.

In 2019, for example, a new state law requiring police to seize firearms at the scene of domestic violence incidents met with “enormous resistance” in law enforcement, said Spokane Police Department Sgt. Dave Adams, who trained fellow officers on this law.

“I had people who were command level yelling at me in training,” Adams said. “Just generally speaking, most of my co-workers are people who are, ‘I’ve got my Second Amendment right. You’re not going to take my guns away. I don’t care what a local court says, the U.S. Constitution overrides.’”

It took until this past year for many agencies like Spokane to start implementing it more proactively, he added.

“These are state mandates,” Adams said. “If you’re in law enforcement and you’re not OK enforcing the laws as written, you have to really reconsider whether or not this is going to be the career for you.”

In August 2024, four weeks after the Kitsap County court found that Leitz had surrendered all of his guns, Berg met with a Mason County detective about her reported sexual assault. Berg told the detective that she feared Leitz still had firearms, according to the sheriff’s office report. She explained how Leitz had shot and killed their family’s two dogs earlier that year, before the protection order was put in place, which Leitz admitted to in a court hearing.

The detective said she would look into it, and later emailed Berg that Leitz had surrendered two guns.

That’s “definitely not all of what he has,” Berg replied.

Two weeks later, after receiving no response, Berg followed up again. “I’m very concerned he may go off the deep end,” Berg wrote. “I know for a fact he didn’t give up all his guns.”

The detective reached out to Leitz and his lawyer, but they didn’t cooperate with her investigation and Leitz was never interviewed, according to the sheriff’s office reports. There’s no indication that the sheriff’s office tried to verify where those other guns were.

Another four months went by. Finally, Berg’s mom, Kelly Walker, submitted a complaint against the sheriff’s office in December, accusing them of mishandling the surrender order. Her complaint fell to the responsibility of Jason Dracobly, then the department’s chief criminal deputy.

Dracobly himself had been ordered to surrender guns to the Mason County Sheriff’s Office back in 2013, when he was a sergeant at the agency. His ex-wife had accused him of domestic violence and anger issues, including threatening to shoot a man she was texting with. The court granted her a restraining order and found that “irreparable injury could result” if Dracobly wasn’t ordered to give up his firearms. He surrendered various hunting rifles and handguns to his co-workers, court records show, but his ex-wife raised concerns that he had not given up three of his guns, including an AR-15. Dracobly, who denied the domestic violence accusations or that he violated the surrender order, eventually got his guns back and continued climbing the ranks in the department.

Dracobly’s internal investigation into Walker’s complaint concluded that her accusations were unfounded. His own divorce had no impact on his review of Walker’s concerns, which, he told InvestigateWest, was “handled objectively and based solely on the facts and information” available to him at the time.

“We do not know what other firearms he may or may not have,” Dracobly’s report said about Leitz. “Yes, he can lie to us. We have no evidence or proof currently that he has physical control of any more firearms.”

Berg says she has shipping information for the AR-style shotgun and a December 2023 video taken by Leitz of herself shooting it, but the Mason County Sheriff’s Office never asked her for proof. According to Sgt. Rowe, that wouldn’t give them enough evidence to search Leitz’s home for prohibited guns anyway. To obtain a search warrant, the Fourth Amendment generally requires that law enforcement have a factually grounded belief that evidence of a crime will be found in that location.

“From my understanding, there is absolutely next to nothing that would give us probable cause to violate somebody’s rights and go into their home and their free space,” Rowe said. A time-stamped photo of a person holding a gun after being subject to a surrender order might give police more tread, he added. “But it’s difficult.”

Dracobly, now the undersheriff, told InvestigateWest that neither Walker nor Berg provided information about specific firearms or their current location, and a general claim that someone “has many guns” isn’t enough to justify a search warrant. It’s critical to have recent information, as opposed to older statements that have lost evidentiary value, he noted. He also emphasized that under state law, it’s up to the courts — not law enforcement — to verify whether people are telling the truth.

It’s not uncommon that survivors know about a partner’s guns but don’t have recent evidence, according to Sandra Shanahan, program manager of King County’s enforcement unit. “Those things are not great fact patterns, necessarily, to get a police officer out there on a warrant,” she said.

But Shanahan and other experts say there are many other actions that police and courts can take. They can look for evidence of previous gun purchases, recent gun ownership or social media posts displaying guns, for example, which could be enough for a judge to determine that a person is not in compliance and ask for further proof.

It’s a lack of communication between police, prosecutors and courts that’s the problem, said Natalie Nanasi, a Southern Methodist University law professor whose research focuses on effective firearm surrender strategies. The solution, Nanasi said, “really can be something as simple as one or two people who are within a county’s court system who are flagging these cases, who are following up on them, who are making sure that everybody who needs the information has the information.”

At the Spokane Police Department, Sgt. Adams reads each domestic violence report that comes across his desk, he said. The volume is daunting. Spokane County has one of the highest reported rates of domestic violence in Washington, with 6,998 offenses in 2024 — making up 11% of the state’s total, according to the Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs’ annual crime report. More than half of those offenses were handled by the Spokane Police Department.

When Adams reads a report that has even “the whiff of a mention of a firearm,” he routes it to Simeral, the YWCA’s domestic violence firearms analyst. Simeral and Spokane police officers explain to accused abusers that surrendering weapons doesn’t mean their guns will be destroyed or sold, but rather stored by law enforcement for safekeeping.

Many people simply state that they have no guns, which Simeral said is often not accurate. To get to the truth, she dives into their history. She checks if the person has legally purchased a gun from a licensed dealer. She works closely with local pawn shops to spot firearms that aren’t supposed to be there. She scours social media accounts for recent pictures of guns and reviews past police reports for mentions of firearms. Then she presents this information to the court.

“If we tell them that we fear that there are some firearms outstanding, and we’ve got some good, tangible evidence to prove that, the courts hold that very highly. They will not just say, ‘You’re in compliance because you say so,’” Simeral said. “We’re way, way beyond that.”

Simeral and Adams say their success comes largely from the city’s decision to invest in the problem. Spokane also has a federal grant and is spending it on costs like increased police training and overtime pay for officers to serve firearm surrender orders during off-duty hours.

In 2017, before Spokane began receiving the federal dollars, 36 firearms were collected, according to data provided by the YWCA. This is despite Spokane courts issuing 3,000 surrender orders that year, representing a 1% collection rate in a state where an estimated 42% of households own guns.

Compliance has now surged, with 2,568 firearms collected from 2020 to 2023, according to the YWCA. That number continues to rise — over 600 guns have been removed this year alone.

Now, it’s unclear if the funding will exist past 2026. To the surprise of some victim advocates, the Office on Violence Against Women under the Trump administration did not release a notice for future grant applicants this year. The office says it plans to do so next year, with the caveat that “any planned funding is always subject to available appropriations and other factors,” it wrote in a statement to InvestigateWest.

Spokane remains committed to prioritizing the issue even if their federal funding stops — advocates secured a grant through the state Department of Commerce to continue their work, according to Sally Winn, YWCA Spokane’s director of legal services.

If you value this type of reporting, help us continue producing high-impact investigations that drive real-world change.

Yes, I support local news!King County, home to Seattle and the state’s most populated county, has found similar success. After launching its firearms enforcement unit in 2018, people subject to domestic violence protection orders became 3.3 times more likely to relinquish at least one firearm or other dangerous weapon, according to a 2023 study by University of Washington researchers. Gun violence prevention experts across the country say other states should look to the unit as a model.

“Laws don't implement themselves,” said Shanahan, the unit’s program manager. “Do we get every gun from every person? Absolutely not. We sure try.”

It wasn’t until August 2025, a year after Leitz was first ordered to surrender his guns, that the Kitsap County Superior Court convened a hearing on Berg’s claims that her ex-husband had not complied.

It was Berg’s chance to present her proof to the court. But without an attorney or enforcement experts like Simeral or Shanahan to assist her, the shipping information and video of the AR-style shotgun were never considered — she didn’t properly send those documents to the court, her emails show.

With little proof to show that Leitz had other guns, a commissioner quickly signed an order finding him in compliance, ending the hearing within minutes.

Leitz, meanwhile, said the hearing was “just another pain in the ass.” He’s frustrated by his mounting legal fees and the repeated requirements for him to prove he can’t access guns. “It’s nothing new for a nasty divorce like this,” he said.

Although state law requires courts to hold compliance hearings as soon as possible after a surrender order is served, and whenever there’s any indication that the order’s subject still has firearms, victim advocates and attorneys say they often don’t happen. In Spokane, courts frequently skipped compliance hearings until the city started focusing on the issue, Winn said.

“Now, the judges and commissioners are infinitely better about setting compliance hearings where they consider actual evidence and not just taking the abuser’s word for it,” Winn said.

Statewide, inconsistent recordkeeping across state courts makes it nearly impossible to track whether courts are properly holding compliance hearings and confirming that all guns were turned in.

“It is actually very, very difficult — and I’m going to say infeasible — to be able to measure all of those separate parts,” said Alice Ellyson, an assistant professor at the University of Washington who researches firearm surrenders in the state.

Courts are still figuring out what penalties to impose when a person refuses to comply, Simeral said. In 2022, the Spokane County District Court found a man named Jesse Jones in contempt of court for stating that he had no firearms despite “overwhelming evidence” to the contrary — including videos of his “secret bunker” behind a hidden door that had gun ports and firearms hanging on the wall, court records show. When Jones failed to prove that he no longer had access to those weapons, a judge hit him with a $150 fine.

The case was a “really big deal” for establishing consequences for not complying with an order, according to Simeral. The goal is to avoid overly punitive measures while still encouraging compliance.

Leitz has maintained, even after the protection order, that he never abused Berg. He also denied the sexual assault allegation that Berg reported in July 2024. (“You can’t rape the willing,” Leitz told InvestigateWest, asserting that photos of Berg’s black eye and bruised arm following the alleged assault were from Berg bumping into walls while drunk.) The Mason County prosecutor’s office said it is still reviewing the rape allegation.

Without his guns, Leitz said his farmwork is more difficult. While he used to be able to shoot cows to put them out of their misery when they injured themselves, he now has to bludgeon them to death with a hammer or wait for a butcher to come slaughter them.

“It’s a lot more gruesome,” Leitz said. But he feels like he has no alternative. “My kids mean more than the firearms do to me, and I gotta be 100% compliant for everything or else I won’t even be able to see my kids.”

Berg still feels that she and her kids are in danger as long as his other guns remain unaccounted for, and plans to keep raising the issue in court.

“My anxiety is off the charts. I’m scared of him,” Berg said. It’s why she got the protection order in the first place. “But of course, it’s just a piece of paper.”

The story you just read is only possible because readers like you support our mission to uncover truths that matter. If you value this reporting, help us continue producing high-impact investigations that drive real-world change. Your donation today ensures we can keep asking tough questions and bringing critical issues to light. Join us — because fearless, independent journalism depends on you!

— Jacob H. Fries, executive director

DonateCancel anytime.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters and never miss an investigation.