Most WA federal rulings found immigrant detentions flouted due process

In 2025, Washington federal courts granted petitions challenging detention more than half the time

Sixty years of heavy traffic by logging trucks, along with trips by forest managers and recreation-seekers have taken a toll on roads that run through Northwest forests.

Tens of thousands of miles of those roads are crumbling, sending sediment and other pollutants into rivers and streams. Fish don’t like that, and many people in the Northwest really don’t like it, which is how the federal Legacy Roads and Trails Program began a few years ago.

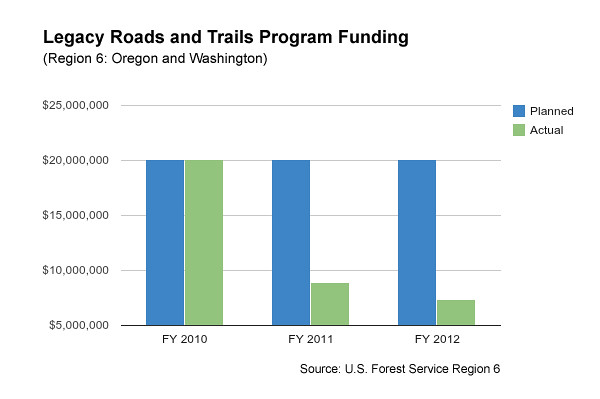

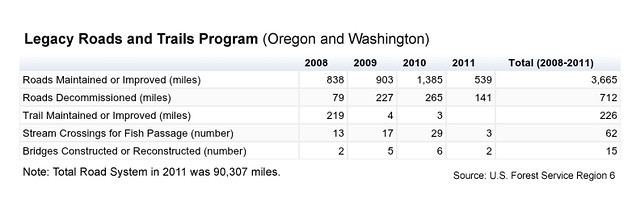

A coalition of 18 groups formed the Washington Watershed Restoration Initiative. They lobbied Congress and, in 2008, pried loose about $8 million to start chipping away at the federal forest road maintenance backlog in Washington and Oregon. The federal dollars peaked in 2010, but have been cut by more than half even though the roads continue to deteriorate and pollute the region’s waters.

The drop in federal funding is frustrating, said Tom Uniack of Washington Wild, one of the founding groups in the Washington Watershed Restoration Initiative. “What really is important is to keep some funding coming into the program, to continue that commitment.”

The maintenance backlog for Washington and Oregon’s federal forest roads is big. To put the roads in “like new” condition would cost an estimated $1.1 billion, according to Rick Collins with the U.S. Forest Service, Region 6.

Other funding sources for forest road work also have been shrinking, including the money commercial forest users pay. The 2012 Budget from all road work sources is not quite $30 million, which is about 18 percent of the funding available in 1990. That doesn’t even cover the $42 million it would take if the Forest Service’s regional offices were to perform basic, routine annual maintenance sufficient to keep the roads open and safe for travel.

“These roads are providing public access to forests, and they also have high aquatic and environmental risks,” Uniack said. “Sediment goes into rivers and watersheds and affects people and fish.”

Sediment is especially dangerous for salmon and steelhead species — many of which are listed as endangered or threatened. Sediment:

The physiological impacts are bad enough, but sediment also can make fish a little psycho, or in scientific terms, sediment can have negative behavioral effects.

University of Washington researchers have described these problems.

By decommissioning obsolete roads and maintaining and stormproofing others, the Forest Service and its local partners are able to reduce the sediment load to waterways. Several Legacy Roads and Trails program projects have stopped sediment from pouring into Northwest waters and restored blocked fish passages. (See the before and after photos below.)

In southeast Oregon’s Malheur National Forest, a culvert was both a jump and a velocity barrier for fish trying to move through a watershed. A new bottomless culvert solved both of those problems.

Source: U.S. National Forest Service, Region 6

An undersized road-stream crossing in the Olympic National Forest was replaced by a new bridge through the Legacy Roads and Trails program.

Source: U.S. National Forest Service, Region 6

The story you just read is only possible because readers like you support our mission to uncover truths that matter. If you value this reporting, help us continue producing high-impact investigations that drive real-world change. Your donation today ensures we can keep asking tough questions and bringing critical issues to light. Join us — because fearless, independent journalism depends on you!

— Jacob H. Fries, executive director

DonateCancel anytime.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters and never miss an investigation.