Free training: How to access police employment & misconduct data in the PNW

If you cover criminal justice in the Pacific Northwest — or want to — we’re hosting a free virtual training that may be useful to you and your newsroom

Woman whose allegations sparked others to speak up says Idaho still must do more to create "just and humane" system

For nearly a year and a half, Andrea Weiskircher has been pleading with prison officials, state leaders and law enforcement to look at the evidence.

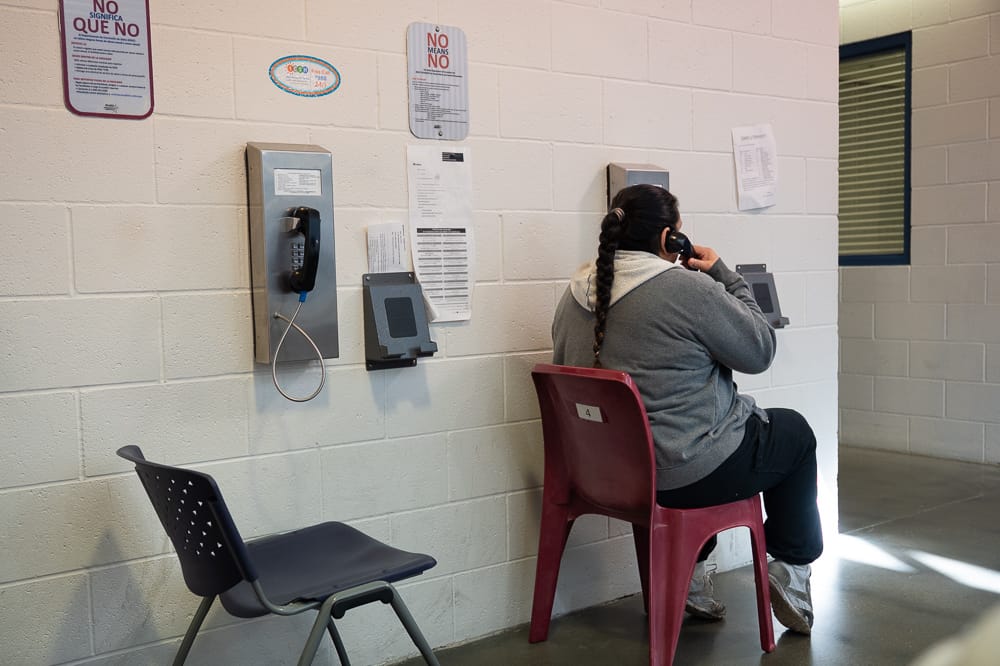

In the summer of 2024, Weiskircher accused five Idaho prison workers of sexually abusing her while she was incarcerated. She had sexually explicit texts, Facebook messages and emails from correction officers and a prison delivery man, Weiskircher told investigators. Any sexual contact between an inmate and prison staff — even voyeurism and harassment — is prohibited by federal standards designed to protect people in custody who are vulnerable to sexual extortion by workers.

But no one in a position to help believed her. Until now.

In a Nov. 21 email, Department of Correction Director Bree Derrick told Weiskircher that after reviewing only “a handful” of those messages, prison system investigators were able to substantiate Weiskircher’s allegations against one of those men, Joseph Mena. The decision to reopen the case comes after a series of reports from InvestigateWest exposing shoddy investigations into complaints like Weiskircher's.

Weiskircher accused Mena, who packaged and delivered commissary items to Idaho prisons, of kissing her while she was incarcerated at South Boise Women’s Correctional Center, bringing her tobacco and other contraband, and propositioning her after she was released. Mena, who no longer works for the prison system, did not respond to calls and messages from InvestigateWest for this story. When reached by phone in September, Mena denied the allegations.

Department of Correction investigators can’t conduct criminal investigations, only administrative ones, which means Mena likely won’t face any consequences unless law enforcement also reopens a case against him. But for Weiskircher, the new finding means someone believed her, and that was worth the fight.

“I feel like we won,” Weiskircher told InvestigateWest. “It's because we all did it together and we didn't give up. They had to fix it. They had no choice.”

Derrick told Weiskircher that the “finding was just made this week, and I hope demonstrates our commitment to thoroughly investigating your claims, including all relevant evidence.”

There is still a long way to go to create a more “just and humane” system for people in state custody, Weiskircher said. Weiskircher's decision to report the abuse unwittingly inspired seven other women to report their abuse to the Department of Correction last summer. Those allegations were among dozens uncovered in a series from InvestigateWest that revealed a decade of unchecked sexual abuse by staff at Idaho women’s prisons. As part of the yearlong probe, more than two dozen women told reporters how they were raped, assaulted, coerced and harassed by Idaho prison workers while they were incarcerated. Some refused to file a report, fearing retaliation. And those who did said they were the ones punished — placed in segregated housing and ostracized by other inmates and staff.

Since 2020, there have been at least 59 documented allegations of staff sexually abusing imprisoned women, InvestigateWest found. Many of those complaints, like Weiskircher’s, were marked as unfounded following little investigation by the Department of Correction. A prison system spokesperson would not share whether any other investigations have been reopened since the news reports were published.

In Weiskircher’s case, the Department of Correction and Idaho State Police originally marked the allegations as unfounded or “determined not to have occurred,” according to a form sent to Weiskircher from the prison system explaining her case was closed. She sent letters and emails objecting to the decision and offering the evidence she had on her phone. But her appeals were dismissed until the InvestigateWest reports were published in October, including one article highlighting Weiskircher’s fight for justice.

In response to the reporting, Gov. Brad Little ordered the Board of Correction to review sexual abuse cases and the prison system’s public records request process. Advocacy groups have condemned the state’s failure to protect women in its custody, calling it “shameful” and “horrifying,” and demanded immediate action. And at least one state lawmaker is looking for ways to improve prison policies and state law to protect inmates.

Since she was released to drug court in June, Weiskircher has become an even more vocal advocate for women like her. She has written to lawmakers and the governor imploring them to implement solutions that have increased safety for inmates in other states, including:

For victims of rape in Idaho, there is no time limit for when the accused can be criminally charged — unless the victim is an inmate. Sexual contact with a prisoner, the felony charge meant to protect people behind bars from abuse by prison staff, must be filed within five years of the assault. But in some cases, victims are still in custody when that clock runs out, leaving them two options: Report their abuse while they remain under the authority of the person they accused, or forfeit the chance to see their abuser punished.

Like most of the women who reported their abuse last summer, Weiskircher waited until she was no longer in the custody of the Department of Correction, limiting her opportunities for justice. Of the five men she accused of sexual abuse, the statute of limitations has expired on allegations against at least three of them. Weiskircher’s allegations against Mena, the former prison delivery man, remain within the legal time constraints. Even though kissing is prohibited by federal standards and by Idaho prison policy, Mena can’t be charged for allegedly kissing Weiskircher under the current state law designed to protect inmates from staff abuse because it only criminalizes sexual contact involving someone’s genitals.

“The current legal and institutional framework in Idaho does not impose sufficient punitive consequences on staff who abuse incarcerated people,” Weiskircher wrote in a Nov. 25 email to lawmakers and Gov. Little. “Without mandatory fines or similarly strong accountability, some abusive guards may view the risk as little more than a career setback — not a serious deterrent.”

Despite the legal limitations, Weiskircher is pushing the prison system and state police to reexamine all five men she accused.

Federal law mandates that the Department of Correction perform an administrative investigation anytime staff sexual abuse is reported. If prison investigators find policy violations, the department can fire, suspend, demote or otherwise discipline staff. And it can use the results to improve policies and procedures increasing the safety of inmates. But the prison system lacks the authority to investigate criminal allegations. That falls to Idaho State Police.

The state police only took on Weiskircher’s case following pressure from an Ada County judge. But her claims were not thoroughly investigated, according to case files that the agency provided to InvestigateWest. Detectives merged Weiskircher’s allegations with two other women, even though they accused different men at different prisons. None of the men Weiskircher accused were contacted by police. Weiskircher emailed some of the messages that the Department of Correction used to substantiate one of her claims to a detective, but there was no mention of them in the case files. Her case was closed as “determined not to have occurred” after a detective misrepresented the facts in her case file, claiming that she told him she never had any sexual contact with prison guards — despite an audio recording of his interview proving otherwise.

State police launched an internal affairs investigation into at least one of the detectives who worked on Weiskircher’s case, she and her attorney told InvestigateWest after they met with a lieutenant. Police spokesman Aaron Snell did not respond to questions about the investigation into one of the detectives or whether Weiskircher’s case was being reopened.

Weiskircher met with a Department of Correction investigator Monday who told her he would review all of her evidence and determine if any of her other claims need to be reopened, she told InvestigateWest. In an emailed statement, the Department of Correction said it is “carefully reviewing” evidence shared by Weiskircher and will reopen investigations into her other claims “if warranted.”

None of the men she accused still work for the Department of Correction. However, if her claims are substantiated, the accused could have their officer certifications revoked, a red flag on their record that could prevent them from being hired for another position where they oversee vulnerable people. One of the men she accused is working as a correction officer in Oregon.

For Weiskircher, it’s not only about holding these men accountable. It’s also about holding the system accountable.

“Making them acknowledge they did something wrong is the only way to make them fix it,” Weiskircher said. “I told the truth about all of it. Not some of it. Not part of it. All of it. And I’m not going to stop until they make it right.”

The story you just read is only possible because readers like you support our mission to uncover truths that matter. If you value this reporting, help us continue producing high-impact investigations that drive real-world change. Your donation today ensures we can keep asking tough questions and bringing critical issues to light. Join us — because fearless, independent journalism depends on you!

— Jacob H. Fries, executive director

DonateCancel anytime.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters and never miss an investigation.