Federal lawsuit alleges Bureau of Indian Affairs officers “executed” unarmed Paiute man in Idaho

The lawsuit claims Bureau of Indian Affairs officers lacked jurisdiction when they pursued, killed Cody Whiterock

Mayor Harrell promised law would get Seattle “back on track,” but new street-tree planting data raises doubts

An early-morning door knock roused a snoozing Rebecca Thorley. In the winter chill at her door stood a friendly City of Seattle worker. He gave a heads-up about upcoming street painting in advance of some work on the property across the street, a place Thorley admired for its towering grove of trees.

“What’s going on?” Thorley recalled asking.

“A development,” the city worker said.

“Are you sure?” Thorley asked.

“He said, ‘Sadly, yes,’” Thorley recalled of the doorstep conversation.

“I got a sinking feeling in my stomach,” Thorley said.

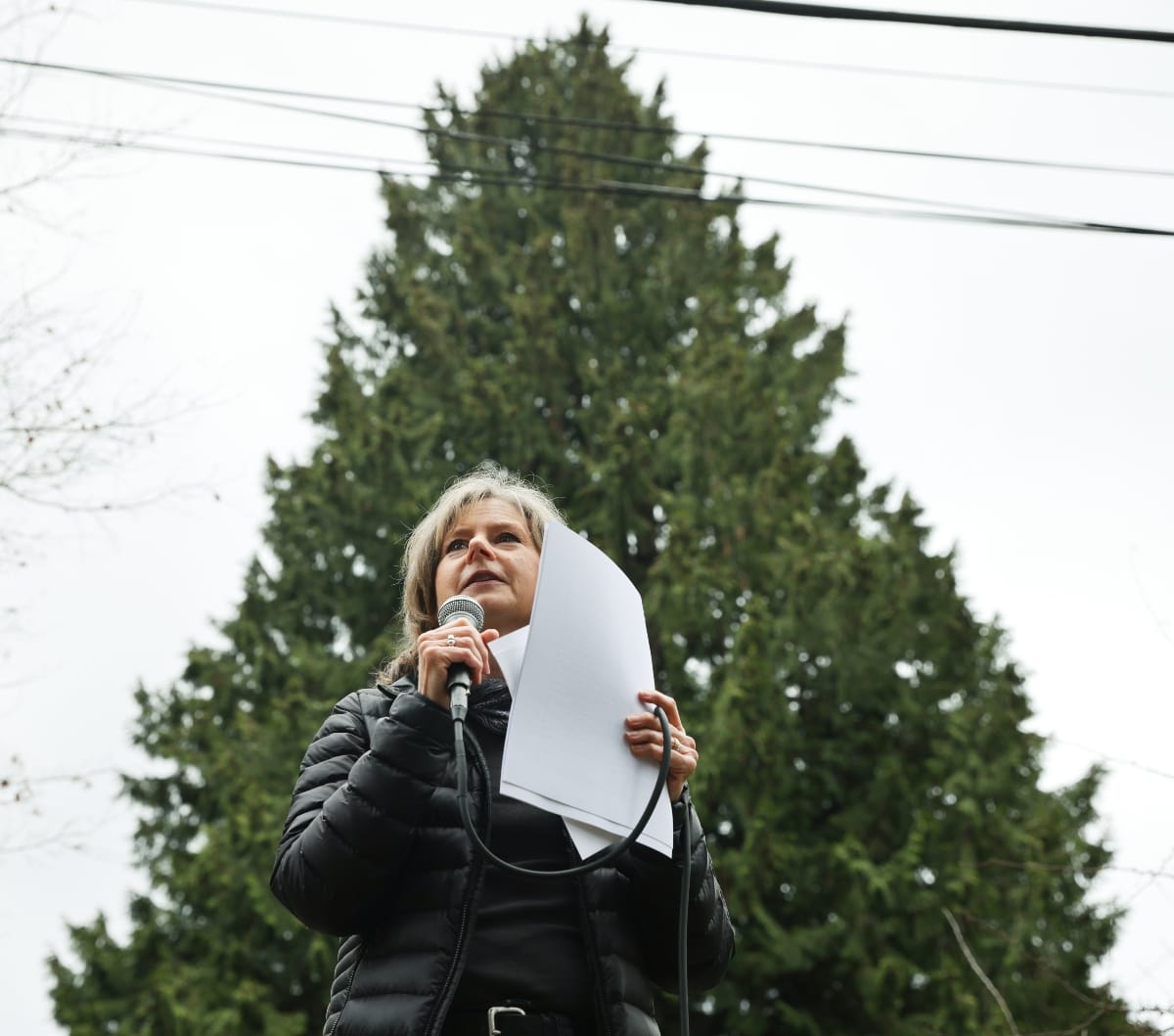

Worried about the birds and bunnies that inhabited the property and about losing shade from the trees, Thorley dove into online research. She emailed the city. She contacted neighbors. Thorley, an attorney, agreed to represent a neighbor living beside the development site, Christy Lommers.

As winter turned to spring, Thorley and Lommers focused on saving a tree at the edge of Lommers’ lot whose roots heavily intertwined with the decades-old grove on the development site, where a tiny home was to be replaced by another house and two “accessory dwelling units.”

In the early summer Thorley returned home to find big red X’s painted on six towering Douglas firs and a large dogwood on the redevelopment site.

When the cutting crew arrived in late July, neighbors called the city. They complained of what they considered irregularities, including allegedly failing to take precautions to protect passersby, records show. For a time, the tree-toppling stopped.

But the cutting crew returned last month. And once again the piney fragrance of sap from just-fallen firs permeated the air. A roaring stump grinder kicked up head-high clouds of dirt and wood chips. It was all over in a few hours. Evidence of the stately trees that stood sentinel for decades vanished forever.

Only one big tree on the development site was spared, the Douglas fir whose roots intertwined most closely with those of Christy Lommers’ fir next door.

For Lommers, preserving those two trees in north Seattle’s semi-leafy Pinehurst neighborhood represents a small win. Yet she is flummoxed that the city allowed the destruction of most of the grove next door.

“I was under the impression that our city has good rules to protect groves of trees,” Lommers said in an interview.

Lommers and her neighbors wonder: How come Seattle’s supposedly strengthened tree protection ordinance is allowing so much tree-cutting?

Similar scenes have replayed in many Seattle neighborhoods since Mayor Bruce Harrell proposed and the City Council approved a developer-backed tree protection ordinance. In 2023, Harrell billed it as an improvement in tree protections because it would safeguard some trees and plant the seeds for many more.

“We must act now to get back on track toward meeting our tree canopy goals and build the climate-forward future we want to see,” Harrell said then.

Seattle set out in the 2000s to increase its climate resilience by boosting tree canopy, and in recent years focused especially on the needs of poorer and more diverse neighborhoods. But after the city’s housing crisis blossomed and made affordable housing increasingly difficult to build, tree-canopy advocates say the updated 2023 ordinance is accommodating developers at the expense of mature trees that can’t be easily replaced.

Numbers from the city show the pace of tree-cutting by builders is escalating, say citizen activists fighting to preserve the leafy tree canopy that inspired civic boosters to nickname Seattle the “Emerald City.” (Harrell declined an interview request for this story, as did Interim Director of the city’s Construction and Inspections Department Kye Lee, whose spokesperson referred readers to an April report.)

Meanwhile, developers and urban-housing activists supporting more housing say sacrificing some trees to help solve the current red-hot housing crisis makes sense. We can plant more trees, they say, and replanting is required when trees are felled.

“We can’t allow tree protection to become a backdoor way to stop desperately needed housing,” Jesse Simpson of the Housing Development Consortium told the City Council in April.

All of this comes to a head this week and next as the City Council adopts a 20-year, state-required plan to handle population growth. The council also plans to adopt a set of related development regulations that would loosen developers’ requirements to provide green space for future canopy regrowth, as well as standards to retain existing trees or plant new ones.

Two years into the administration of Seattle’s long-promised but controversial update of the city’s tree protection ordinance, the tally of trees toppled in the face of development escalated markedly this year, an analysis of city data shows.

Developers operating under the new ordinance cut down about six trees per week on average during the first year the ordinance was in force. By the ordinance’s two-year birthday on July 30 of this year, that number was running at about 58 trees per week on average. (And in August another 293 trees fell. That’s 73 per week.)

The analysis is based on data recorded by Dave Gloger, a retired engineer and Tree Action Seattle volunteer, who started periodically recording the total number of felled trees he retrieved from a city webpage starting in June 2024.

In the wake of the law’s passage, Gloger and other tree-canopy advocates say they have seen a stark difference in the ability of developers to take down trees.

“It’s almost devastating what we’re doing to our city,” Gloger said.

The Tree Action Seattle analysis was compiled by periodically examining a City of Seattle webpage that tracks the total number of trees removed, planted or “protected” during construction, or for other reasons.

The group’s Dave Gloger, who tracked the numbers of removed trees reported by a city webpage starting in July 2024, also filed a request under the Public Records Act for the city’s data behind the webpage. But the data the city delivered did not have any dates associated with the tree removals. Gloger asked the city to provide the dates, but was told the database for which he requested numbers doesn’t include them.

InvestigateWest also asked the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections, which oversees enforcement of the tree protection ordinance, to supply the dates on which the trees in its database were removed. Department spokesman Bryan Stevens replied in an email:

“There are no dates in the database associated with the tree points for our GIS mapping system. Alternatively, you can use the SDCI record number provided in the spreadsheet to research individual projects where trees were removed, protected during construction (i.e., not removed for the construction), or planted. You can research permit activity here: https://www.seattle.gov/sdci/resources/research-a-project"

Gloger began tracking the tree removals nearly a year into administration of the ordinance. At the time 324 trees had been removed because of construction, versus 560 for other reasons, such as homeowners seeking to remove hazardous or diseased trees. In April of this year the number of trees removed for construction surpassed those removed for other reasons, 1,683 to 1,636. As of Aug. 29 of this year, the total removed for construction was 2,583 and for other reasons, 2,075.

— ROBERT McCLURE / INVESTIGATEWEST

Seattle Construction and Inspections Department spokesperson Bryan Stevens said Tuesday that the current total for trees removed by construction is 2,582. That closely matches Gloger’s Aug. 29 total of 2,538. Stevens said 4,561 trees have been planted in association with those construction sites. He noted that more than 90% of trees removed in conjunction with construction are less than two feet in diameter.

Just before the ordinance passed in 2023, the city-appointed Urban Forestry Commission, a panel of experts who volunteer to advise the City Council, called the ordinance “flawed and rushed.” The commission said the process used to adopt it violated the Seattle Municipal Code.

“The proposed legislation appears to have been developed behind closed doors without substantive participation by the (Urban Forestry) Commission and other stakeholders,” the forestry commission said in a letter to City Council members.

2007: City sets goal to increase tree canopy coverage from 18% to 30% in 30 years.

2009: City Council approves “interim” tree protection ordinance, directs staff to write a stronger ordinance for consideration in 2010. Sets up Urban Forestry Commission, a panel of experts to advise the City Council.

2010: City Council fails to take up stronger tree protection ordinance as promised.

2010-2020: Seattle becomes the fastest-growing city in America. Housing costs skyrocket. Low-priced apartments disappear by the thousands.

2016: Study documents Seattle tree canopy coverage at 28.6%*

2021: Study pegs Seattle’s tree canopy at 28.1%, a 1.7% loss since last study. Study also highlights stark differences between the tree canopy in wealthier and whiter neighborhoods and more diverse sections of town where the number of trees lags behind.

2023: Mayor Bruce Harrell proposes, and City Council passes, an updated tree protection ordinance. Passage spearheaded by Council Member Dan Strauss, then chair of council’s Land Use Committee. Strass says the legislation “protects trees in our neighborhoods, and during development, while making space for housing our city, the fastest growing city in the nation, desperately needs.” Strauss tells tree-protection advocates, “I want to continue working with you. …This is not a one-time deal.”

2024: City Department of Construction and Inspections recommends no changes to the ordinance until 2025.

2025: City Council to adopt comprehensive growth plan. Current draft would make it harder than ever to protect trees, according to urban-canopy advocates.

*Not comparable to earlier canopy studies because of differences in methodology

The two-year-old ordinance passed with strong backing by the development industry, as InvestigateWest previously reported, loosening rules to allow builders to cover more ground with development. It requires developers to replace the larger felled trees, but only with short saplings.

When the ordinance passed, the City Council was under intense pressure to produce housing. Renters faced skyrocketing costs, in part because low-priced apartments had disappeared by the thousands. Would-be first-time homebuyers were frequently stymied. Unhoused people’s tents popped up across the city.

All that is still true. So, what now?

Rebecca Thorley and her neighbors had good reason to worry when the trees shading their neighborhood came down Aug. 6. Scientists say trees prevent deaths during heat waves and intercept rains that otherwise would wash Seattle streets’ toxic detritus into local waterways.

The pollutants carried by this so-called “stormwater” compromise the very existence of endangered orcas and salmon, according to wildlife ecologists — the subject of an ongoing legal appeal of the ordinance.

Most residents haven’t heard about the potential effects of widespread tree cutting under the current tree protection ordinance, said Gloger.

“When I talk to people, they say, ‘I thought we had a really strong tree protection ordinance,’ and I explain that there are really two different ordinances, one for private property owners and one for developers,” Gloger said.

“Until a tree is cut down in their neighborhood, they don’t understand what’s going on.”

Here is what Gloger is talking about: The thrust of the 2023 revision of the tree ordinance was to encourage development on private property. The net effect was to shift the burden of preserving Seattle’s tree canopy from developers to homeowners and public lands.

The result is that since July 2023 it’s been relatively easy for developers to cut down trees on the private lands that make up nearly half the city’s land mass. In many cases that’s because the new ordinance authorizes a “tree protection” area that, perversely, protects such a large area of trees’ roots that if planned development would expand over them, removal of the tree is allowed.

On the other hand, the new ordinance makes it significantly more difficult for homeowners to remove trees, compared to the old ordinance.

The city has never achieved its long-held goal of covering 30% of the city with tree canopy by 2037, and in fact at last check was “slowly losing ground,” a 2021 study found, with greater losses in more diverse and poorer neighborhoods.

A big part of the city’s approach to making up for trees lost on private lands being redeveloped is to plant trees on publicly owned land, such as parks and rights of way such as land beside roads.

But that vision was seriously called into question when the Seattle Department of Transportation early this summer released reports showing how hard it will be to actually reach the city’s tree-canopy goal by planting so-called “street trees.”

Transportation department reports on census tracts in four Seattle neighborhoods found that — even if trees were planted in every possible streetside spot — the tree canopy would fall well short of the 30% goal.

The worst case was Sodo, one of the city’s industrial districts, with a current 9% canopy that could be boosted just to 10%. Roxhill could achieve 23.7%, South Park 16.7% and Capitol Hill/Olive Way 20.3%.

And those numbers actually greatly overstate what would actually be possible today, the transportation department reports say. That’s because those numbers anticipate a significant street-side removal of pavement, underground utilities and similarly expensive and time-consuming efforts. Without that, the numbers fall further.

For example, of the 881 potential tree-planting spots identified in South Park, only 40% could be planted today. Available today are 21% in Sodo, 17% in Capitol Hill/Olive Way, and 58% in Roxhill.

“In each of these cases, they are not even getting close to the equity (goal) of 30% canopy coverage,” said architect David Moehring, co-chair of the Trees and People Coalition, who served on the Urban Forestry Commission. “The City Council says they want to focus on low canopy areas. But they’re still going to be short.”

Consider also the expense to plant and maintain the trees. Each tree planted requires thousands of dollars in city expenses, mostly to pay city employees to check on and water the trees. The city Parks Department has pegged that cost at $4,000 per tree (to say nothing of the cost the Transportation Department would incur by removing pavement and other infrastructure to fit in additional trees). In South Park alone, at the rate of $4,000 per tree, it would cost more than $3.5 million.

And what about parks? Mayor Harrell in 2023 issued an executive order that every tree removed from city parks be replaced by at least three trees instead of the previously required two.

Tree-canopy advocates say the idea of planting more trees in the 9% of Seattle’s land area covered by parks is definitely helpful. But those trees often are not near housing, where they need to be to keep residents healthier by intercepting pollution and moderating increasingly common heat waves, among other benefits.

It’s also true the city plans to plant some 40,000 trees over a five-year period, as Harrell announced shortly before the City Council approved the controversial tree ordinance.

“Mayor Harrell has been clear that we must take a holistic approach to maintaining and growing a healthy tree canopy citywide and addressing inequities in canopy distribution while also supporting the housing production needed during a homelessness and housing crisis,” Harrell spokeswoman Callie Craighead wrote in an email. “Seattle’s tree ordinance passed in 2023 strikes this necessary balance, as data shows that over 10,400 units of housing have been added through June 2025 and more trees were planted than removed.”

But tree advocates wonder: What happens for the next two or three decades while those tiny trees are still growing, and residents don’t benefit from their pollution-filtering effects?

As the City Council prepares to take on the state-required growth plan, council members lately have emphasized that housing costs loom largest in their minds.

“We have a housing affordability crisis,” City Council President Sara Nelson told her council colleagues last month. “And we’re not going to be able to subsidize our way out of it.

“So that means we have to make housing easier to build.”

As the City Council sought the public’s opinions on the emerging growth plan in recent months, both tree advocates and development interests professed to want housing and trees.

But tree advocates say the comprehensive plan as currently proposed would accelerate damage to the city’s tree canopy that the 2023 tree protection ordinance allowed.

Under the proposed comprehensive plan, “We are still allowing vast swaths of pavement,” said Sandy Shettler, an activist with Tree Action Seattle. “The trajectory is toward becoming an even bigger heat island.”

The tale of “Astra,” a towering cedar that was two feet across at chest height, best pinpoints how the 2023 tree ordinance helped developers topple big trees, according to Sandy Shettler of Tree Action Seattle.

Documents released to the group under the Public Records Act show developer Take 3003 LLC sought city permits 17 days before the new ordinance took effect in July 2023. With the project still stuck in permitting in December, records show, a city official reached out to an executive at Legacy Group Capital, which had purchased the lot and then sold it to Take 3003 LLC, and, records suggest, was helping manage the project.

The Legacy executive contacted the project architect, suggesting seeking permits under the new ordinance instead, records show, and that afternoon the architect did so. Two weeks later the city sent a list of questions for the developer to answer, records show.

The development was on its way. In coming months neighbors and others staged noisy protests to save the tree beside an unassuming home set behind a white-picket fence. David Moehring, an architect who serves as co-chair of the Trees and People Coalition and a former member of the city-appointed Urban Forestry Commission, reviewed the development’s paperwork. He calculated that the old ordinance required the developer to steer clear of a 60-foot-diameter zone designed to protect the tree’s roots. But under the new ordinance, which includes an “enhanced” root protection zone, that number shot up to a 100-foot-diameter circle. Wouldn’t that further protect the tree?

Not under the new ordinance. The new ordinance actually authorizes taking down trees if development would encroach on the supposed “tree protection” zone. Astra fell on Oct. 22. The property is now listed for sale on the developer’s website. Take 3003 LLC declined an interview request. Legacy did not respond to requests for comment.

— ROBERT McCLURE / INVESTIGATEWEST

Tree advocates point out that climate change is exacerbating heat spells, and argue that it takes decades for newly planted saplings to replace the shading and pollution-intercepting qualities of mature trees.

A powerful force on the other side of the debate is the Master Builders Association of King and Snohomish County, which declined to take part in an interview. Also lining up on that side of the debate is the Complete Communities Coalition, a consortium of builders, business and finance organizations, racial-equity groups and others under the umbrella of the Housing Development Consortium.

Their take: Sacrificing some trees in Seattle beats cutting down suburban and exurban forests. In a city that just blew past 800,000 population and shows no signs of moderating growth, it’s better for the climate to increase density and reduce commutes by car.

They note that Seattle requires trees that are cut down to be replaced. These housing advocates imply that tree advocates are really just anti-growth in a region that has some of the least affordable housing costs in the nation. They ask: Why can’t north Seattle’s leafy and mostly white neighborhoods give up some trees so housing supply can be increased and housing prices moderated? And then plant more trees in southern and more ethnically diverse neighborhoods that have traditionally been more industrial and hence less-treed?

“Of course we want to save every tree and build all the homes we need. But when those goals come into conflict, we must choose housing,” said Simpson, of the Housing Development Consortium. “Because people need a place to live.”

Gloger, the Tree Action Seattle volunteer, is especially dismayed by the general tendency under the new ordinance for developers to clearcut every lot being redeveloped, with little thought to preserving trees.

“I don’t expect (builders) to protect all of the trees, but I would like for them to protect the large ones and the ones that are on the edge of the property that aren’t in the way of development,” Gloger said.

Better design could often provide the same amount of housing, tree advocates argue, and protect many trees. But builders aren’t incentivized to do so.

“I know we need more housing, but the housing I see being built when they cut down these big trees is not affordable,” Gloger said. “They’re big houses that stretch across the property so they can make more money.“

Also arguing for tree preservation is state Rep. Gerry Pollet of Seattle, co-sponsor of HB 1110, which required cities to increase density in housing. The 2023 law has been cited by proponents of the currently drafted comprehensive plan. But Pollet argued in a December 2024 letter to the City Council that the state law also allows the city to require preservation of trees.

“Seattle may, and should, meet its climate and related mature tree canopy and runoff prevention policies through adoption of tree preservation ordinances that preserve from development the best remaining mature tree canopy in the face of dramatic loss of trees in recent years,” Pollet wrote.

The City Council has scheduled a virtual public hearing on the comprehensive plan from 9:30 a.m. to noon on Friday, Sept. 12, and an in-person session starting at 3 p.m. The council is expected to vote on amendments next week.

This reporting was supported in part by the Fund for Investigative Journalism. The story has been updated to reflect changes to the City Council's meeting on Friday.

The story you just read is only possible because readers like you support our mission to uncover truths that matter. If you value this reporting, help us continue producing high-impact investigations that drive real-world change. Your donation today ensures we can keep asking tough questions and bringing critical issues to light. Join us — because fearless, independent journalism depends on you!

— Jacob H. Fries, executive director

DonateCancel anytime.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters and never miss an investigation.