Lawsuit alleges Bureau of Indian Affairs officers “executed” unarmed Shoshone-Paiute man in Idaho

The lawsuit claims Bureau of Indian Affairs officers lacked jurisdiction when they pursued, killed Cody Whiterock

The state had recently expanded the novel program for providing one-on-one career coaching, job fairs behind bars and support for people after release

Thomas Van Hoose had been here before. Nearing the end of his third stint in an Oregon correctional facility on drug charges, he was thinking about what life on the outside would be like yet again.

His first two times exiting prison went about the same way: He got a minimum-wage job, but soon found himself sinking under the weight of the intractable costs of living — rent, utilities, food, child support — that his meager paycheck could not cover.

“I could pay rent, but I can’t pay for utilities, or I can pay the utilities, but food is short. Something like that is always going on,” he recalled. “Once it gets to that point, I start supplementing my income, and in general, that leads me back to drugs.”

Van Hoose, 50, was determined to do it differently ahead of his release in May from Deer Ridge Correctional Institution outside Madras, a city in Central Oregon. This time, he sought assistance from a novel workforce development program inside the prison that put him on track to find good-paying work about six months after he was released.

The program — called WorkSource Oregon Reentry — helped him make a resume, connect with potential employers and map out career goals while still incarcerated. Once released, staff paid the nearly $6,000 in training and licensing fees he needed to secure a job as a truck driver. He now works for Swift Steel, a pipe supplier in Redmond, a city about half an hour south of Madras.

“This is the first time that anybody’s come in and seemed to care,” Van Hoose said. “This program has been my light at the end of the tunnel.”

Launched in 2022 as a partnership between one of Oregon’s local labor development boards and state agencies, the WorkSource Oregon Reentry program provides comprehensive career services to incarcerated adults both as they prepare to leave prison and after release with the goal of steering people towards meaningful employment.

While still incarcerated, participants are able to develop the soft skills needed to find employment — like interviewing, finding job listings and workplace communication. Then, once back outside, WorkSource directs people to open positions they could be a fit for and finances the cost of necessities to work, like gas and licensure, among other things. It’s one of just a handful of workforce programs in state-run prisons and among the first in the U.S. to expand statewide.

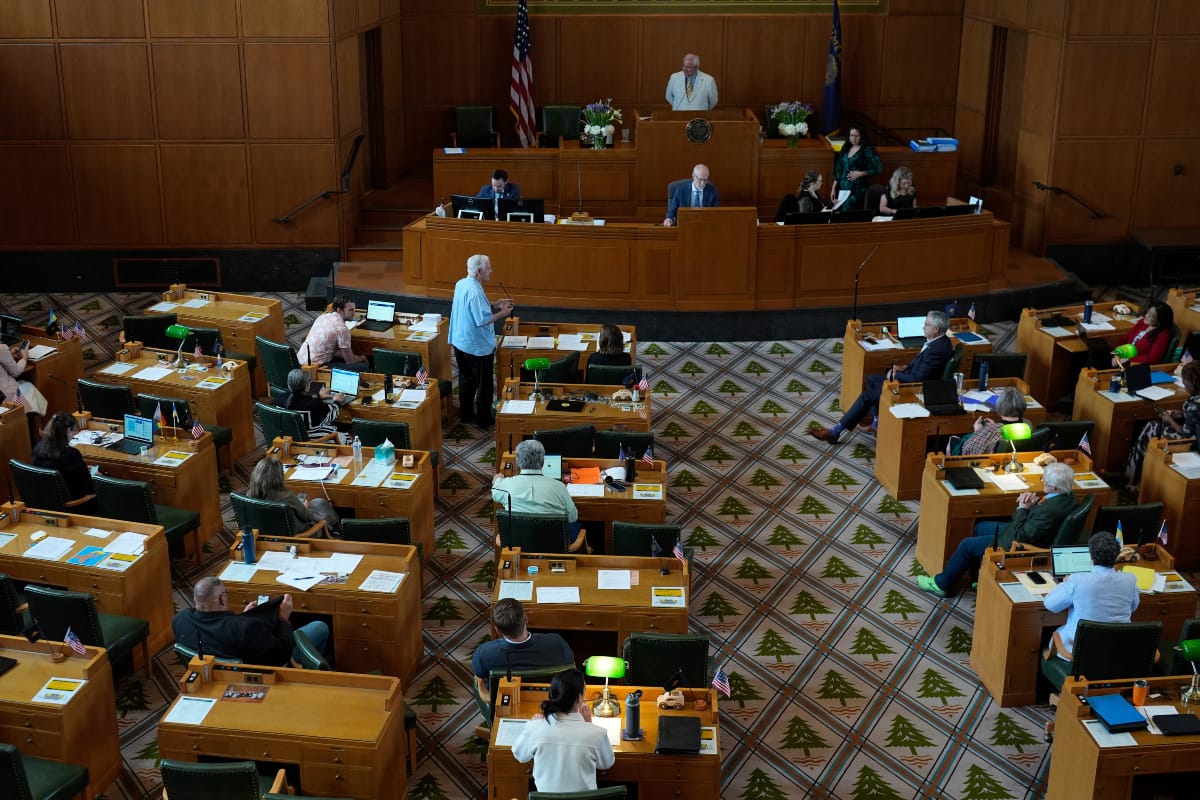

But the program could start to wind down by as early as next spring, after Oregon lawmakers failed this summer to pass a bill that would have allocated $3 million to maintain its operations for the next two years. Up until now, the program has been sustained by roughly $5 million in grant funding from the U.S. Department of Labor and a one-time state workforce investment package passed by the Oregon Legislature in 2022 — dollars that will run out next year.

“This is extremely frustrating,” said Heather Ficht, executive director of East Cascades Works, a labor development board that works with businesses and governments to support local job growth and which spearheaded the WorkSource initiative. “There’s nowhere to turn for more money, the spigot’s off at the federal level and there’s no money in Oregon.”

When the bill to continue the program’s funding was first introduced, it was championed as a bipartisan answer to Oregon’s longstanding skilled trade workforce shortage, one that tapped into a labor force whose full potential had not been realized.

Yet the bill became one of many budget casualties as lawmakers looked to scale back state spending, anticipating future challenges spurred by federal policy changes and a slowing economy. A number of existing programs, like eviction prevention and early childhood education, took significant hits, while new requests stalled.

WorkSource and Department of Corrections staff are currently scrambling to find grant funding to avoid shutting down the on-site services that hundreds of people approaching the end of their prison sentence have come to rely on, namely the one-on-one coaching and guidance that helps people reorient themselves to the labor market after years behind bars.

“The last thing we want is for all this work that we’ve done over the last four years to just go away,” said Amy Bertrand, the Department of Corrections’ reentry and release administrator.

While people can still seek out the WorkSource program outside prison walls, Ficht says making an early connection helps smooth the transition out of prison, giving people the know-how and encouragement to find legitimate work before they become overwhelmed by life on the outside.

“It’s a scary thing to leave incarceration and have nothing,” Ficht said. “So to lose the side of the coin that’s inside is going to impact our ability to actually get clear referrals of people.”

Van Hoose credits the WorkSource program with finally finding a job that pays enough to support himself and start building a life that previously felt out of reach — one where he has purpose and believes in his ability to realize his goals.

“It’s saving me right now from winding up going back to prison and continuing the cycle I’ve been on,” Van Hoose said. “It can save a lot of people from that because it’ll put you in a position to be able to have a decent life, not one of struggle. The struggle is what sends us back.”

The WorkSource Oregon Reentry initiative first launched in 2022 as a pilot program in two of Oregon’s correctional institutions — Deer Ridge and Warner Creek — to provide one-on-one career training to people leaving prison. A few other states have similar employment training programs, such as the “Breakthrough” employment training program that Colorado offers in just five of its 21 institutions.

Starting as early as six months before release, the program walks incarcerated Oregonians through developing a resume and cover letter, how to interview, financial planning, workplace communication, identifying career goals and finding job opportunities. Many participants can feel directionless during prison and need support and encouragement to think positively about the future and their work experience behind bars, according to Ficht.

“It’s a confidence builder,” she said. “There is hope for you. You’re going to be alright, we’re going to help you.”

Once participants leave prison, WorkSource provides them with essentials like gas and phone cards, tools and work clothes, and it covers the cost to obtain licenses and certifications, which can be difficult for someone transitioning back into society to foot on their own.

That includes people like Shane Sherman, who was released from prison in June and began working for his brother’s construction company in Central Oregon, but did not have adequate workwear for winter, when temperatures regularly fall around 40 degrees or below.

“If I didn’t have these clothes, I’d kind of be screwed,” Sherman said.

Beyond their efforts with inmates, WorkSource connects with employers like Sherman’s brother to source job leads and walk them through the benefits of hiring formerly incarcerated people, including federal tax incentives. The program also brings employers inside state prisons for job fairs, providing crucial face time with program participants.

Data about the relatively new program’s effectiveness is so far limited. During its first two years in operation at Deer Ridge and Warner Creek, of the 277 people who received career guidance in prison and were released, 138 continued to engage on the outside. And 98 of those people, or about 71%, were employed or in training for skilled work after leaving prison, according to East Cascades Works.

Many participants in the pilot years weren’t able to continue the program after prison because they returned to a part of the state outside East Cascades Works’ service area, Ficht said — a reason the board pushed for the statewide expansion.

To expand the program, WorkSource secured $4.9 million in federal and state grant funding in 2023 to bring on additional staff and build computer labs at every prison. The last of those new facilities came online earlier this year, allowing the program to work with up to 900 inmates a year — about 13% of people released from Oregon prisons annually. Since July 2024, 995 people have enrolled in the program across the state, according to East Cascades Works.

WorkSource staff currently spend several days a week coaching people inside each correctional facility, staffing which will go away without a new funding source. The Department of Corrections said it may try to use video conferencing to replace some of this programming, but it’s not clear if the department has resources to do it.

The bill lawmakers considered earlier this year, HB 2972, would have funded the program’s staffing and operations for the next two years.

The measure cleared its first legislative committee with bipartisan support. But the appropriations committee shelved it, along with most new spending requests, because of uncertainty over how federal policy would affect Oregon’s 2025-2027 budget.

The extent of this impact became apparent after President Donald Trump signed a spending and tax cuts package in July that Oregon estimates will reduce state tax revenue by $888 million over the next two years, on top of significant cutbacks in federal contributions to key programs like Medicaid and food stamps.

State economists estimated in a November forecast that the tax revenue hit will leave Oregon with a $63 million budget deficit, a smaller gap than initially expected after receiving more in corporate income tax payments than originally anticipated. State agencies are now being asked to look at ways to cut spending ahead of next year’s shorter legislative session in the spring, when lawmakers are expected to finalize budget changes. Reconsideration of funding for programs like WorkSource that failed to pass this year is unlikely during the session.

State Rep. David Gomberg, D-Lincoln, one of the sponsors of HB 2972, said he may ask the Legislature to fund the reentry program again in 2027, when the next budget will be considered.

It’s not clear if the state’s budget woes will be in the rearview mirror by then. According to Gomberg’s office, appropriators only had about $500 million this year to pay for new programs or increase spending on existing ones, but upwards of $5 billion in requests.

“This is a good idea,” Gomberg said. “But I also have to recognize that when folks are out of work, when people can’t find housing, when our schools are suffering and we’re having trouble finding the dollars to put out wildfires, it’s going to be difficult to get people to invest in long-term strategies.”

“Do we have enough money to pay for it?” he continued. “The answer at the end of the day was no.”

Over the years, Oregon has introduced a wide array of programming into correctional facilities, aiming to promote rehabilitation and lower recidivism. Yet access to these initiatives — and their success in making a difference in inmates’ lives — varies significantly across the state.

Lower security facilities in the valley to the west of the Cascades, near Salem or Portland, have more resources available to offer community college courses or apprenticeship programs to inmates. But those programs are much smaller or are entirely absent at prisons in rural parts of Oregon.

“It feels unattainable for some people because there’s such a small number of people that can be accepted,” said Bertrand, the Department of Corrections’ reentry and release administrator, noting resource constraints and supervision requirements can limit the department’s ability to offer these in-prison initiatives.

Even with these programs, significant gaps still remain in translating what participants are learning into future employment once they leave prison. For one, navigating online job hunting can be overwhelming after years with limited access to technology. Programs also seldom touch on how to discuss a conviction with a potential employer or where to find work.

Difficulty meeting basic needs after release — like stable housing, reliable transportation and phone service — can similarly make it harder to find and maintain employment.

“It's almost impossible to find a job if you can't get calls from employers that you're applying for jobs for, or transportation assistance to get around, or knowledge of employers that will accept what background they may have,” said Chase Bissett, director of employment services for Central City Concern, a social services provider in Portland.

Paired with requirements like background checks or restrictions on where a person with a criminal conviction can work, these barriers push unemployment rates among formerly incarcerated people in the U.S. far above that of the general population.

The Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit advocacy group, estimated in a recent study that the average unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people in 2008 — the most recent year nationwide data from state prisons was available — was over 27%, above the peak of overall unemployment during the Great Depression. Unemployment was even higher in the first two years after exiting prison, sitting around 32%.

When formerly incarcerated people are able to obtain work, as is often a requirement of their post-release supervision conditions, it tends to be a low-paying position with little job security, keeping them well below the poverty line without much opportunity for economic mobility.

“The No. 1 contributor to recidivism is poverty,” said Wanda Bertram with the Prison Policy Initiative. “When people can’t be sure where their next paycheck comes from, that’s going to push them to desperate actions.”

One study on recidivism in Missouri found those who were unemployed after leaving prison were twice as likely to return compared to those who were able to obtain a full-time job.

Oregon does not formally track connection to full-time employment as part of its three-year recidivism estimates, and because the WorkSource reentry program is only a few years old, the program does not yet have comparable data on how participation impacts recidivism. East Cascades Works had hoped another two years of operations would allow them to demonstrate the program could help reduce recidivism.

“The program had just been getting up and going,” said Teresa Weir, director of programs for East Cascades Works.

Without the WorkSource program, it would fall to the Department of Corrections’ transition coordination team and reentry counselors to connect people leaving prison to employment services, according to Ficht and Bertrand. But those teams are already overwhelmed trying to assist the hundreds of people released from prison every day, and don't have the capacity to connect with employers and personally guide people through their job search.

“Despite the best intentions and wanting to connect people with employment, we couldn’t really get there without the help of [WorkSource],” Bertrand said.

In 2024, Rudy Stalford was preparing to return home to Bend in Central Oregon after a few years behind bars. He was worried what it would take to get back on his feet when his November release date rolled around. All he had was the $5,000 he had saved working in a call center in prison, which would only barely tide him over, and winter would be setting in.

“I didn’t want to waste any time. I just wanted to hit the ground running,” he recalled. So, he signed up for WorkSource’s program at Deer Ridge.

At first, it was hard to accept the resources WorkSource provided, since he was raised believing he had to shoulder everything life threw at him on his own. “I felt guilty by taking a pair of boots, a gas card and a phone card,” he said.

Now, more than a year after leaving prison, Stalford works two jobs, including a position as a tumbler operator at Mission Linen Supply in Bend, which came from a recommendation made by the WorkSource team.

Stalford hopes to save up enough to one day start his own woodworking business, using skills he first learned from his father and continued to hone while incarcerated. He knows how important that first helping hand was to his success after leaving prison and laments the possibility that others leaving Oregon prisons won’t have the same opportunity.

“People need help sometimes,” he said. “We're all human beings. We want to succeed. We want to live and thrive and be different people.”

The story you just read is only possible because readers like you support our mission to uncover truths that matter. If you value this reporting, help us continue producing high-impact investigations that drive real-world change. Your donation today ensures we can keep asking tough questions and bringing critical issues to light. Join us — because fearless, independent journalism depends on you!

— Jacob H. Fries, executive director

DonateCancel anytime.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters and never miss an investigation.