These Washington educators have lost or surrendered their teaching license for alleged misconduct

A searchable teacher misconduct database compiled by InvestigateWest fills gaps in the state’s public-facing records

Workers say exposure caused serious health issues including a hospitalization and a miscarriage

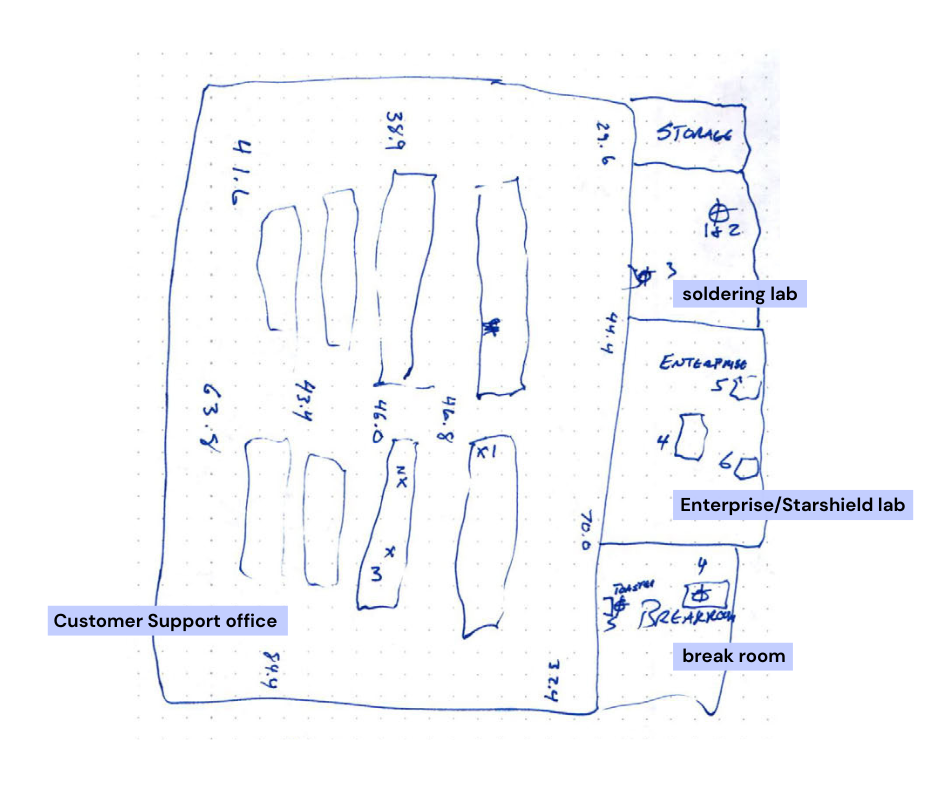

In 2023, at a SpaceX campus just northeast of Seattle, the company converted a small office room into a production lab to help make satellites for global internet service provider Starlink.

The impromptu lab was known by some within SpaceX as the “Starshield” lab — referring to a special Starlink satellite program offered to government intelligence agencies that uses encrypted messaging services. Lab technicians worked under a recent corporate mandate to “triple production,” one later told a Washington state Department of Labor & Industries compliance officer. The workers in the Starshield lab and an additional lab next door handled lead and solvents that contained dangerous chemicals linked to cancer and reproductive toxicity.

Yet the lab shared a ventilation system with the SpaceX customer support hub, which at any given time contained up to 50 workers who did not wear any protective equipment and who were never told about the potential exposure, records obtained by InvestigateWest show.

SpaceX safety managers internally reported concerns with the lab as early as October 2023, flagging that the lab lacked proper ventilation and that workers were leaving the door open to help the circulation. But more than 1,700 pages of public records obtained by InvestigateWest, along with interviews with former workers and others familiar with the situation, reveal how Redmond’s SpaceX site, under pressure to increase production for Starlink, did not take action to protect workers potentially exposed to dangerous chemicals for more than a year until the state got involved, then fired workers who dared to speak up.

SpaceX did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Starting in 2024, customer support workers reported symptoms that matched the known toxic effects of exposure to several chemicals used in the lab. Douglas Altshuler, a former Starlink customer support associate who lived with Crohn’s disease, experienced an allergic reaction that caused one of his eyes to swell shut. A doctor later attributed his condition to “an unknown chemical exposure,” according to a complaint he submitted to Labor & Industries. SpaceX also received more than two dozen other internal complaints from workers who reported headaches, eye irritation and allergic reactions. Altshuler’s complaint said that he was concerned the chemicals caused two women in the customer support office to have miscarriages and another man to have a liver transplant. InvestigateWest spoke with several former workers who confirmed that at least one woman miscarried. The man who allegedly had a liver transplant could not be reached for this story.

“Management was aware that (multiple individuals) were pregnant,” said Melissa Kiss, a former customer support employee. “It’s not just about me, it’s about other people too. … These people have a family, they have kids, they have bills to pay.”

Altshuler went on medical leave and reported the company to Labor & Industries, which opened a four-month-long investigation in November 2024. The state cited SpaceX for three violations including for failing to evaluate workers’ exposure and for having lead dust found on shelves in the soldering lab. It fined the company $6,000. SpaceX appealed, claiming that L&I had no basis for the violations. L&I upheld its decision, and SpaceX appealed again to the state’s Board of Industrial Insurance Appeals. A final decision on the appeal is likely before the summer.

The story in Redmond mirrors issues in other facilities owned by Elon Musk, the world’s wealthiest man. Workers have publicly criticized Musk’s companies for a culture where safety is not prioritized and talking about unionizing can get you fired.

Records from the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration show the site in Redmond has more violations than any other SpaceX facility, even greater than the Hawthorne, California, campus where the number of employees is more than six times greater. The seven violations in Redmond stem from the past two years and include things like not properly training employees working with lithium batteries and not ensuring workers wear foot protection when near crushing hazards.

The site’s most recent state inspection wasn’t the first time workers at the Redmond facility feared chemical exposure. In 2021, L&I received complaints that lab technicians in another building allegedly worked with paint thinners without proper ventilation or protective equipment. A third party industrial hygienist company performed sampling and found all levels to be well below regulatory limits. L&I did not issue any violations.

SpaceX sites across the country failed to report workers’ injuries for years, including in Redmond, according to a 2023 Reuters investigation. Tesla, too, failed to correctly report injuries, and California’s regulators found the company violated health and safety laws more than 40 times in five years, a 2018 Reveal investigation found. In 2024, SpaceX made it on the National Council for Occupational Safety and Health’s “Dirty Dozen” list, a yearly report of reckless employers created by a federation of worker groups across the country, after documenting that SpaceX workers had suffered “crushed limbs, amputations, chemical burns and a preventable death.”

SpaceX has also taken aim at the National Labor Relations Board after a group of employees filed an unfair labor practices claim, arguing in a lawsuit that the board's structure is unconstitutional.

“You have extreme wealth at the top versus extreme risk at the bottom,” said Jessica Martinez, executive director of the National Council for Occupational Safety and Health. “This is a quintessential profit over people. Corporate ambition is prioritized, and safety protocols are bypassed or even discouraged.”

SpaceX’s Redmond campus is located in a business park in a newly developed part of Seattle suburbia, surrounded by forests and trails. It includes a production facility for Starlink, the money-making arm of the company which provides global internet service through a network constellation of over 7,000 satellites.

Kiss, who recently had moved from Austria, started at Starlink customer support as a German bilingual associate in January 2023, and she grew to believe Starlink was making a difference by helping countries in crisis.

The company sends free satellites to disaster-stricken areas, including in Ukraine, making it a pivotal tool in the Russia-Ukraine war. SpaceX uses Starlink profits to fund development of the “Starship,” a reusable rocket that’s planned to carry 100 passengers. Its first crewed mission to Mars is scheduled for 2030.

“It wasn’t your typical customer support job,” Kiss said. “A lot of it you think, ‘Wow, that sounds like science fiction,’ but if you think about how helpful you could be (to) countries that are at war or where there’s some catastrophe, flood, whatever and you’re supplying them with internet. I mean, to connect them to their families, that’s really cool.”

The customer support role had perks. There were lavish Christmas parties, a company chef with a rotating menu. Employees also received private stock in SpaceX, a potentially lucrative benefit as the company is preparing to list on the stock market with an over $1 trillion valuation.

“I loved that job — it was the best experience of my life,” Kiss said.

“At the same time, it was the worst experience of my life.”

The customer support office is in a commercial building across the street from the rest of SpaceX’s campus. The 30,000-square-foot building includes five other businesses: a pediatric clinic, cable manufacturer, pediatric dentistry, mortgage lender and holistic medical clinic, all of which share a common hallway and bathroom with SpaceX employees.

Kiss didn’t anticipate that working in the customer support hub could potentially expose her to dangerous chemicals. None of the customer support employees were given protective equipment. Yet from 2023 to 2025, she and other customer support employees say the door to the Starshield lab was frequently propped open, allowing the air to flow directly into the employee break room and customer support office.

“It’s not good practice to leave those doors open to non-industrial areas,” said Kevin Milani, an industrial hygienist who previously worked for the San Francisco Department of Public Health. “Any industrial area should have its own separate ventilation and definitely be closed off to break areas. Those are supposed to be safe places for employees where they can go and enjoy their food and not have to worry about being exposed to something.”

Technicians in the lab wore personal protective equipment and used toxic adhesives and solvents on electronic navigation systems that would later guide satellites, and they cured parts in an industrial oven, records show. In a second lab adjacent to the customer support room, workers used a tin-lead alloy to join wires onto circuit boards. While lead soldering is rare in most industrial applications because less toxic alternatives are available, it’s still used in aerospace because it’s less prone to cracking under heat stress.

This type of work requires specialized equipment to filter the air for workers exposed to fumes and lead-laden dust. Yet records show the company’s own safety team voiced concerns about inadequate ventilation in the lab, long before customer support employees began reporting health issues.

The first complaint came in October 2023, when one safety manager reported the soldering lab had “no proper ventilation.” A month later, another manager noted in a SpaceX safety portal that the air circulation in the Starshield lab was “not sufficient” and that the door was kept open to let out heat from a thermal oven.

Milani said that proper ventilation would require at least a fume extractor, a device that protects workers from inhaling toxic lead particles. More than a year after the report, there was still no fume extractor in place in either lab, according to state inspection files.

There were other signs the facility was ill-equipped: SpaceX safety management found the soldering room lacked waste containers and storage for chemicals, and every fire extinguisher in the building was expired.

Despite these internal flags, work continued as normal.

By February 2024, customer support employees began reporting health issues.

That month, Kiss told a customer support manager in a Microsoft Teams message that the air was dry and employees were experiencing itchiness and redness in their eyes and requested a humidifier, according to the state’s inspection records. The manager never replied.

Another employee told InvestigateWest they constantly raised questions about the headaches people were getting and requested that the carpets be cleaned. That employee spoke to InvestigateWest on the condition of anonymity and said that upper management moved their office to the other side of the building, the farthest away from the lab, but there were no modifications for the customer support employees.

“I definitely felt dizzy after work, and I wasn’t sure why,” the former employee said. "(The lab) needed to not be in that building at all."

L&I began investigating the chemical exposure in November 2024, after Altshuler went to the doctor for a swollen eye. Altshuler did not respond to InvestigateWest’s inquiries, and his attorneys declined to comment.

Meanwhile, employee complaints were piling up in SpaceX’s safety portal, records from L&I show.

“These past few weeks my coworkers and I have been getting medical side effects working in our building,” one customer support employee wrote. “Headaches, eye irritations, eye swelling, eye twitching. … This week the medical side (effects) are increasing with no solution in sight.”

Another said, “Management is aware of this, as well as HR and yet we are not being accommodated.”

One customer support employee reported eye irritation “due to a vent above their desk.” Management reportedly told the employee to take sick leave, according to another safety report.

A lab worker tagged a customer support manager in an internal complaint demanding that SpaceX install a local exhaust system to prevent vapors from “dispersing into the rest” of the office, but the manager didn’t offer any accommodations.

That same week in November, a health and safety manager again reported that several benches inside the lab had soldering equipment, yet there were still no fume extractors or containers for lead and other hazardous waste. It had been over a year since the issue had first been reported.

The state’s inspection was scheduled for Dec. 17, 2024, a month after L&I opened the investigation. SpaceX chose the date and L&I agreed. The inspector informed Haley Laing, a former SpaceX safety manager, how the sampling to test for chemical exposure would take place. Three customer support employees and three Starshield lab technicians would wear air pumping devices for eight hours to determine the level of certain contaminants they could be breathing in.

That’s not enough time to properly test for an exposure, Milani said. Instead of one snapshot of eight hours, exposure assessments should involve “multiple days of testing,” he said. That will give a “better picture of what an exposure actually looks like.”

After knowing since October 2023 that there were concerns from their own safety team, SpaceX management only took action to improve the lab’s ventilation in the days leading up to the inspection.

According to notes from state regulators, after they opened the investigation, SpaceX installed three fume extractors with carbon filters in the Starshield and soldering labs. Former employees say the safety team also inspected the ceiling and deep cleaned the area.

Those ventilation measures were in place by the time the state inspector showed up to test for sampling.

The day of sampling, L&I performed a screening test for common contaminants and lead.

All sampling results came back below regulatory limits, except for surface samples that were taken near the soldering station. L&I found lead in a concentration 18 times greater than the state or federal government allows.

In February 2025, L&I cited SpaceX for the lead exceedance, amounting to a $6,000 fine. It also issued a violation for failing to conduct an employee exposure test for airborne contaminants, but because L&I performed testing, SpaceX avoided a fine for that violation.

Just a week before the state’s chemical testing, Kiss watched a lab tech place a small metal part in the toaster oven. Kiss, wanting another witness, rushed back to the cubicles to grab Altshuler, who had just returned from medical leave. She took pictures and sent them to Richard Caldwell, the L&I industrial hygiene compliance officer.

Any employee who worked in the building and may have used the toaster oven could have ingested harmful chemicals after that incident, Caldwell said in a February 2025 report. Up to 50 employees out of more than 200 overall worked in the customer support hub at any given time. Regulators found the company in violation of safety protocols, but because the company removed the toaster oven after the incident, it avoided a fine.

One lab worker also told Caldwell during the inspection that the Starshield lab went from having two workers to eight at any given time, according to records of the inspection. Two former employees said Caldwell later told them during the inspection that having that many workers in such a small room was not safe, though the issue did not result in any citations. L&I says that it does not have the jurisdiction to cite SpaceX for a maximum occupancy violation.

The state agency, though, did not test for all of the chemicals in use in the lab. It didn’t test for the silicone rubber compounds found in adhesives that are linked to reproductive toxicity or for formaldehyde in an epoxy primer that is known to cause cancer.

At least four of the untested chemicals found in lab products were labeled as “toxic to reproduction” — having the capacity to harm fertility or an unborn child, according to safety data sheets that contain regulatory information on the chemical makeup of industrial products, suggested use and toxicological effects. Most of the chemicals could cause serious eye and skin damage. Five chemicals in the epoxy primer were carcinogenic. The product’s safety sheet suggested it should only be used with proper ventilation and that repeated exposure to high vapor concentrations could cause respiratory irritation and permanent brain and nervous system damage.

One employee said their co-worker’s miscarriage happened in the woman’s first trimester. That’s a “critical window for reproductive toxicity,” according to Joshua Robinson, a reproductive toxicologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

One of the products used in the lab contained D4, a type of siloxane. It’s classified in the European Union as a substance of “very high concern” in damaging fertility, and the Environmental Protection Agency notes that reproductive health is among the areas most sensitive to exposure, Robinson said.

Robinson said the employee’s miscarriage is “very concerning” but it would be difficult to link it to the exposure without more biomonitoring data. L&I hadn’t heard of the miscarriage at the time of the inspection.

Because lab workers weren’t doing any sanding or grinding that would create dust, L&I didn’t test for any other chemicals being used in the lab, said Matt Ross, L&I public affairs manager, adding the activity falls “outside the scope of the inspection.”

And D4 was removed from the state’s list of Chemicals of High Concern to Children in 2017. There is no federal exposure limit for this chemical.

“A lot of industrial use chemicals do not have occupational exposure levels because they are being created faster than governmental industrial hygienists can test their safety,” Milani said.

Even though regulators don’t have occupational exposure levels for D4, Milani said SpaceX could have taken precautions to protect workers. The company could have taken the same protective measures that are taken with other regulated chemicals similar in composition, a common practice known as “occupational exposure banding.” The National Institute of Occupational Health and Safety has an open-source banding tool to determine what precautions can be used to keep people safe.

“There are plenty of tools that should have been accessible to the folks at SpaceX to do (banding), even if it was a siloxane or something else that doesn’t have an occupational exposure level currently,“ he said. “It’s something that they should know about.”

Altshuler, the employee who was diagnosed with an “unknown chemical exposure,” was terminated in January 2025. SpaceX security paraded him out of the building in front of all his colleagues to “make a point,” he later said in a retaliation claim. He claimed to be a top performer in the customer support department.

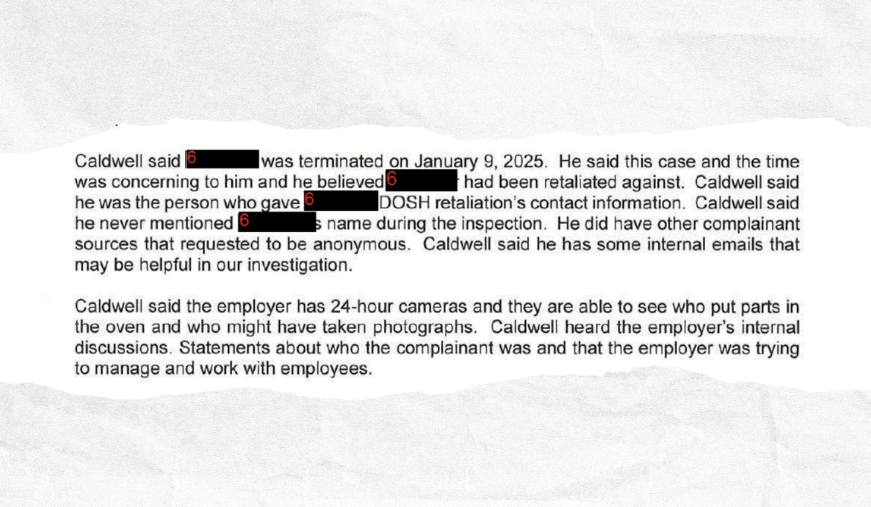

Caldwell, the industrial hygiene officer, told an L&I officer who investigates retaliation that Altshuler’s sudden termination “seemed retaliatory to me,” according to notes from a meeting between Caldwell and the L&I officer.

Caldwell knew SpaceX had 24-hour cameras and “heard the employer’s internal discussions,” in which SpaceX management was discussing “who the complainant was,” the report said — though in reality Altshuler wasn’t the complainant.

A week after Altshuler filed a retaliation complaint in February, he withdrew it and the agency ceased any further investigation.

When L&I released its citations to SpaceX in February 2025, employee health and safety manager Haley Laing emailed all employees in the affected building about the results. But the email misrepresented the findings.

Laing said all sampling tests performed by the Department of Labor & Industries could not be detected or were below the exposure limit, even though lead was found in concentrations 18 times greater than what’s allowed. Though L&I issued a total of three citations, Laing only mentioned two citations without specifying what they were for. And she assured employees that SpaceX was “confident” its workplace procedures abided by the law. Laing did not respond to emails or phone calls from InvestigateWest.

SpaceX appealed L&I’s citations, stating they weren’t supported by “relevant facts or applicable law,” according to the company’s appeal. L&I upheld its decision to issue the violations, and SpaceX appealed again to the Board of Industrial Insurance Appeals, a state agency that hears employer challenges to L&I’s decisions.

Kiss, frustrated with the lack of transparency and accountability, decided to email SpaceX President and Chief Operating Officer Gwynne Shotwell anonymously.

“SpaceX has terminated several employees in an apparent effort to silence dissent," Kiss said. “Morale in the support organization has significantly declined, as dedicated employees are leaving, being wrongfully terminated, feeling mistreated and abandoned.”

Kiss said Shotwell never replied. A few days later, Kiss sent another email to Laing, Shotwell, human resources, SpaceX’s legal team and all employees in the customer support building. This time, she used her name.

“Upon hire, I was never informed (not verbally, nor in writing), that I would possibly be exposed to or working near chemicals in this building,” Kiss said. “Such actions are illegal.”

A few days later, Kiss received a phone call on her day off. She was fired.

At least one other anonymous customer support employee, whose identity InvestigateWest could not confirm, filed a complaint to L&I, the fourth the state received from SpaceX's customer support employees within four months.

The employee said customer support workers were worried about “preemptive measures” taken by SpaceX before the investigation to improve “the overall health state of the office.” The complaint also alleged that SpaceX management refused to provide workers with copies of the inspection findings and that a worker who shared concerns about a “serious hospitalization due to ‘toxins’ found in their blood” — and filed a report about it — was fired for performance issues.

“The employees who are unaware of the lead contamination are proceeding to work as usual,” they continued. “If they are not made aware of their months of exposure, it will be more difficult for a blood test to detect accurate levels and diagnose possible future health concerns.”

L&I “did not find anything” in the complaint that warranted a follow-up, a spokesperson said. It also confirmed that SpaceX management posted its inspection results, but they were located in a different building across the street from the customer support department.

Former employees have said that several people were fired after raising concerns to management. Kiss and one other employee confirmed their termination with InvestigateWest.

Altshuler tried to sue SpaceX. His case, filed in King County Superior Court, moved to arbitration in June. Kiss, and many other employees, were not aware they signed an arbitration agreement as a condition of their employment.

Arbitration agreements have become increasingly common for big corporations as a private and less costly way to handle legal disputes with employees. It’s a closed door process in which legal claims are decided by a third-party expert instead of a jury. Workers can still receive a settlement from arbitration, but the amount is typically significantly lower than if a jury was involved.

Martinez, the director of the National Council for Occupational Safety and Health, criticized the use of mandatory arbitration as eliminating workers’ right to a jury and a strategy by employers to avoid public knowledge of the real conditions that workers face.

“Arbitration strips workers from the right to publicly challenge unsafe conditions,” Martinez said.

Kiss saw herself building a career at SpaceX. She, like many others, uprooted her life to take the job. She received stock awards and was promoted twice in less than two years. But after her termination, she questioned everything.

“Nothing was done even though there was ample evidence,” Kiss said. “The managers knew. They could have just said we’re going to temporarily move you to a different space or work from home, but there was just no care whatsoever. You never know what long-term effects this is going to have, too. I’m fine now. Who knows what’s going to happen in the future?”

The story you just read is only possible because readers like you support our mission to uncover truths that matter. If you value this reporting, help us continue producing high-impact investigations that drive real-world change. Your donation today ensures we can keep asking tough questions and bringing critical issues to light. Join us — because fearless, independent journalism depends on you!

— Jacob H. Fries, executive director

DonateCancel anytime.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters and never miss an investigation.