Washington scrambles to regulate license-plate cameras that could aid stalkers

As lawmakers debate how to rein in these cameras, sheriffs, civil rights groups and transparency advocates are clashing over how much access is too much

It was a good year for accountability in the Pacific Northwest, as InvestigateWest published major investigations and deep-dive journalism on issues affecting people across the region. Here are six stories out of Washington that we broke in 2024.

Constitutional sheriff builds volunteer posse

In rural Klickitat County, Sheriff Bob Songer — who has drawn national attention for his belief that sheriffs have the constitutional authority to decide which laws they will enforce — has been building a posse of volunteers nearly 10 times larger than the number of deputies, InvestigateWest’s Paul Kiefer reported. The posse is accountable to Songer alone, and he has warned that if the federal or state government tried to confiscate civilian firearms, he would use the posse to fight back. The posse has drawn concerns from residents worried about Songer’s association with far-right movements, as well as the potential liability to the county in the event of a violent encounter between a posse member and a citizen.

Sixteen-year-old Kit Nelson-Mora went missing in autumn of 2021, but police didn’t begin investigating the case for more than a year. Reporter Kelsey Turner looked deeply into the disappearance of the teen and documented the gaps in the responses of police, social workers and others in the months after the teen vanished. Kit, who has ancestral ties to the Penticton Indian Band in British Columbia, was one of 58 missing children and 128 missing Indigenous people in Washington — the most of any state in the country.

Three years, no investigations

In 2021, Washington lawmakers created the nation’s first independent state agency tasked with probing police killings and other uses of force — a step intended to build trust among the public and hold police officers accountable when they use deadly force. Reporter Melanie Henshaw found that the new Office of Independent Investigations, beleaguered by hiring challenges and bureaucratic obstacles, had yet to open a single investigation more than three years later. The pace is especially frustrating for families of people shot by police who were cleared by local prosecutors in disputed cases — three of the five such cases under review by the office involved the deaths of Native Americans, who are shot by police at dramatically higher rates than white people.

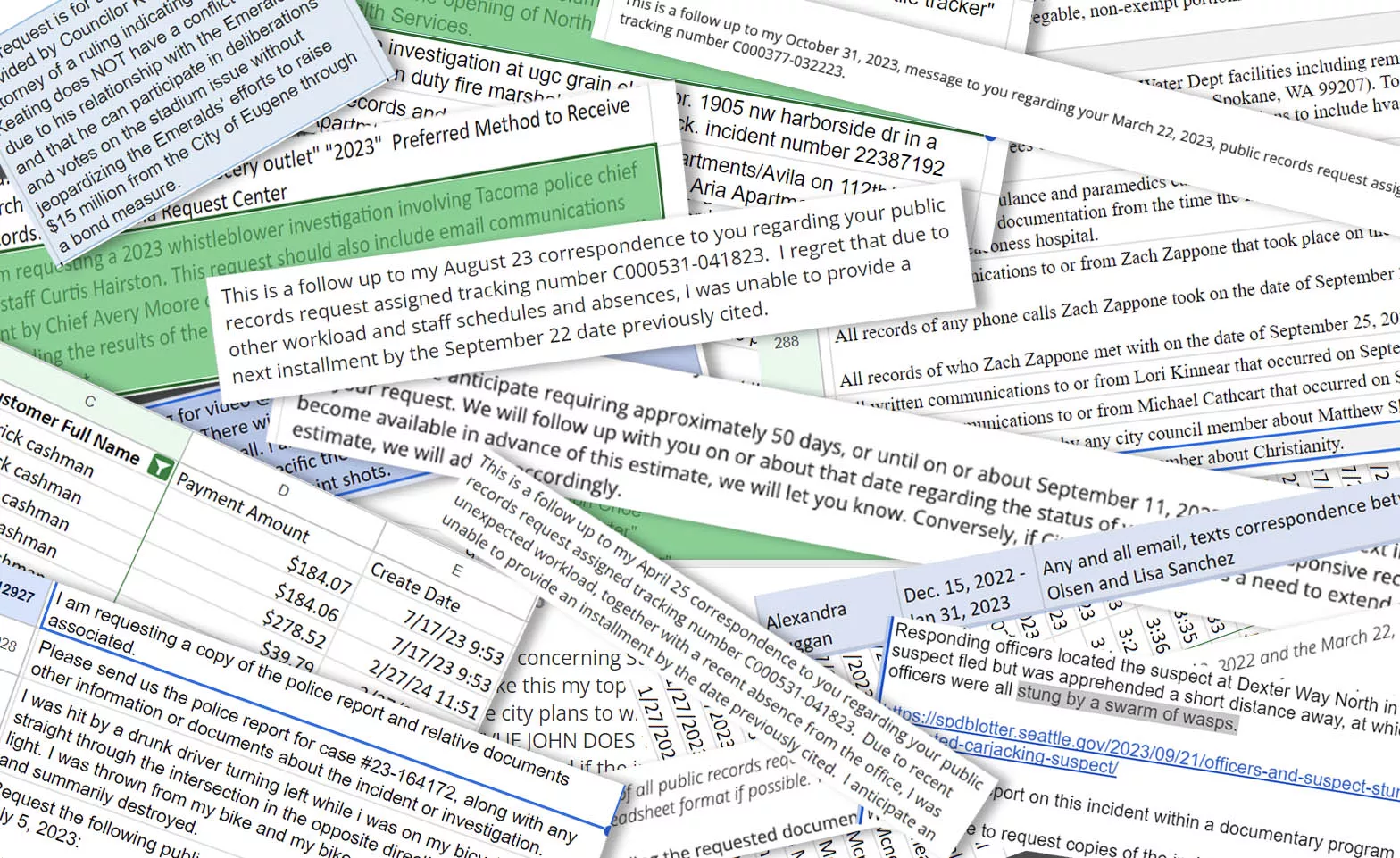

InvestigateWest’s Daniel Walters set out to test the responsiveness of local governments to public records requests — seeking public documents from the five biggest cities in Washington, Oregon and Idaho. Spokane was by far the slowest, taking 129 days to provide its records log, which was six times slower than any other city tested. It’s a common problem for the city, which took six months or longer to respond to roughly 100 requests between November 2022 and November 2023. In response, Mayor Lisa Brown committed to hiring new staffers and the city embarked on an audit of the city’s handling of public records.

Victims of sexual assault felt left out of plea deals

When Jay heard that the man she had accused of sexually assaulting her would be pleading guilty to a lesser charge, she said, “I felt like I didn’t get the justice I deserved.” She’s not alone: Nearly two-thirds of sexual-assault cases handled by King County prosecutors in recent years ended with defendants entering pleas to lesser crimes, InvestigateWest’s Kelsey Turner found. Such deals often deny victims legal protections and go against their express desire for a just resolution to their case. Washington lawmakers have passed bills in recent years attempting to expand protections for victims and to provide specialized training for prosecutors dealing with sexual assault.

Tribal citizens on hook for medical bills when feds don’t pay

Citizens of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation sometimes receive a surprise in the mail: a medical bill that should not be theirs to pay. But when the federal Indian Health Service — responsible for carrying out the government’s obligation to pay for the health care of Native Americans — doesn’t cover the expense, tribal citizens are left with a choice between paying it themselves or taking a hit to their credit rating, reporter Melanie Henshaw discovered. It happens thousands of times a year: An IHS service provider refers a patient for treatment outside the system, the underfunded agency doesn’t pay the bill, and patients pay the price — literally.

The story you just read is only possible because readers like you support our mission to uncover truths that matter. If you value this reporting, help us continue producing high-impact investigations that drive real-world change. Your donation today ensures we can keep asking tough questions and bringing critical issues to light. Join us — because fearless, independent journalism depends on you!

— Jacob H. Fries, executive director

DonateCancel anytime.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters and never miss an investigation.